Life at 16,700 Feet: Inside Peru’s Sky‑High Mining Town

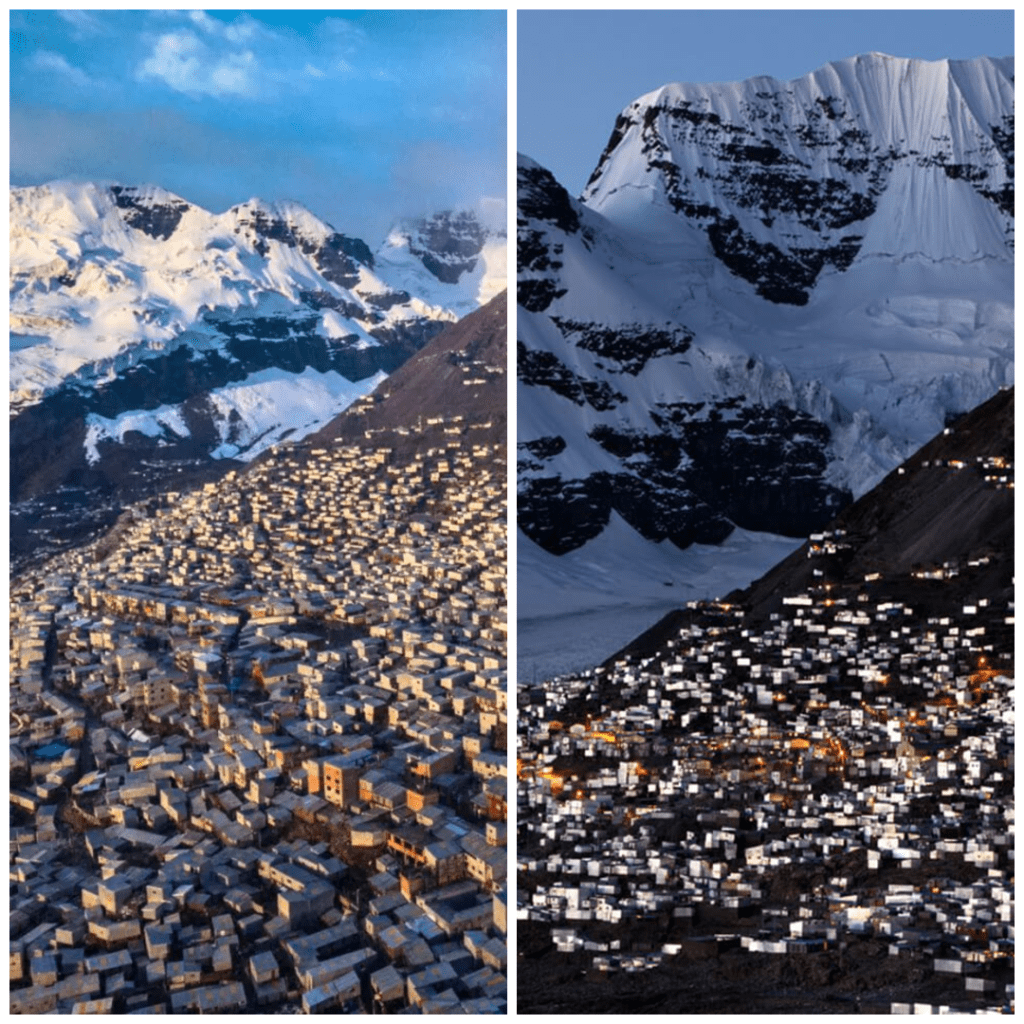

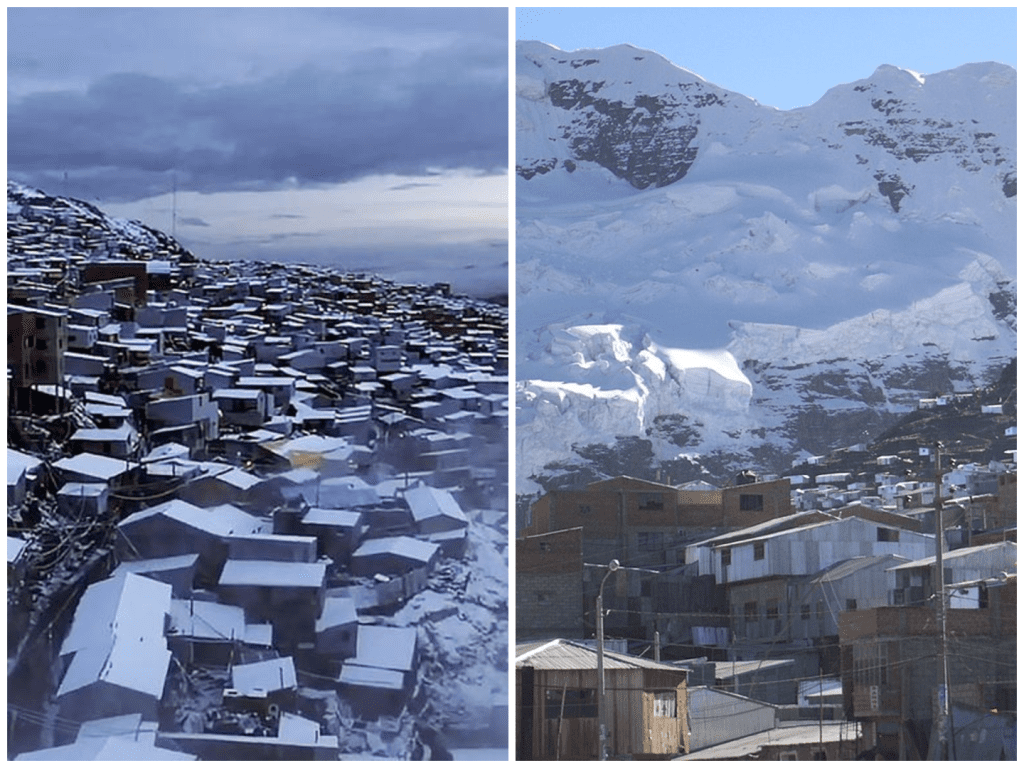

I remember stepping off the rickety bus and feeling the air—thin, crisp, almost hollow. We’d just arrived in La Rinconada, perched on the slopes of Mount Ananea in Peru. At roughly 5,100 meters, or 16,700 feet above sea level, this isn’t your run‑of‑the‑mill mountain village. This place is known as the highest permanent settlement on earth, and what life looks like here is something that stays with you long after you leave.

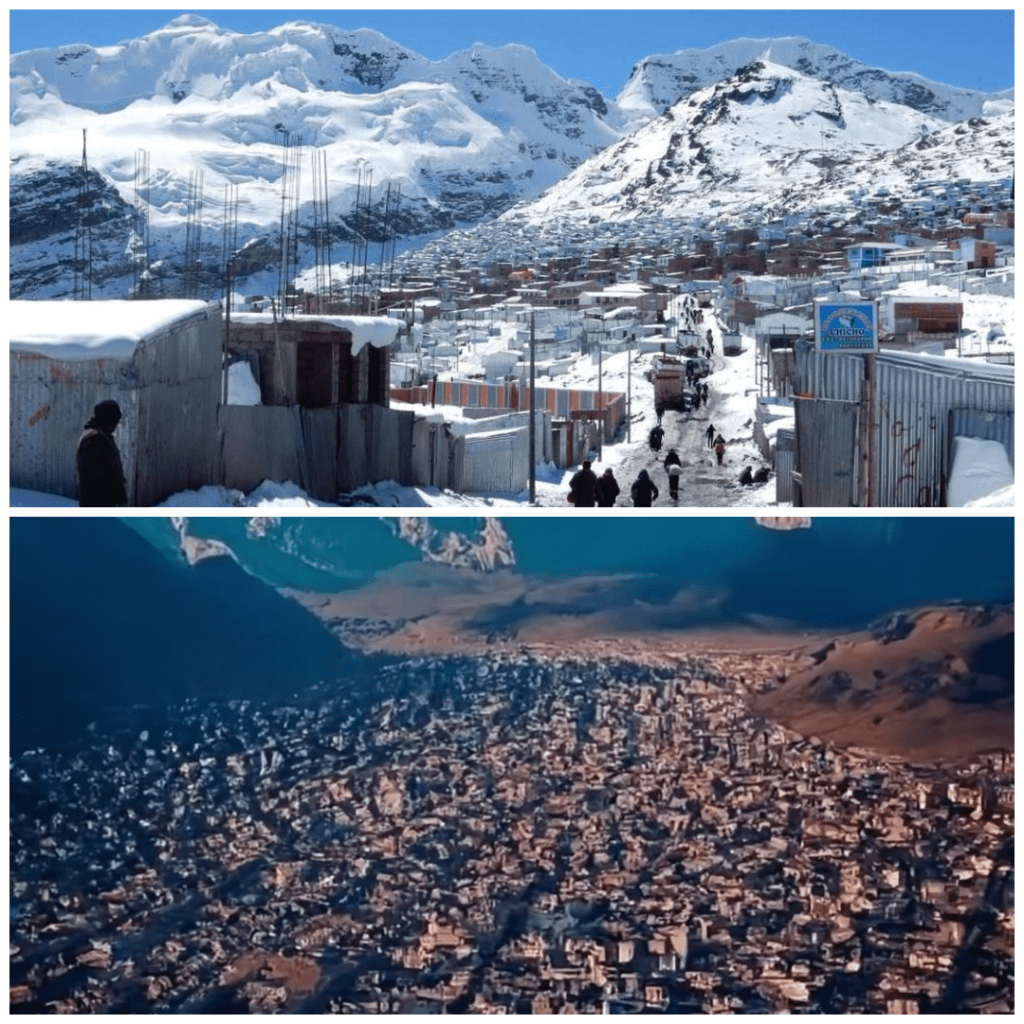

When I first read about La Rinconada in a National Geographic report from the early 2000s, it talked about a gold rush that turned a small mining camp into a town of 30,000 by around 2009. Official figures from 2017 said about 9,700 people lived here. No matter the number, what matters is that this settlement exists in an environment most of us find impossible. The average annual temperature barely hikes above freezing, and snow blankets the landscape as often as blue sky appears.

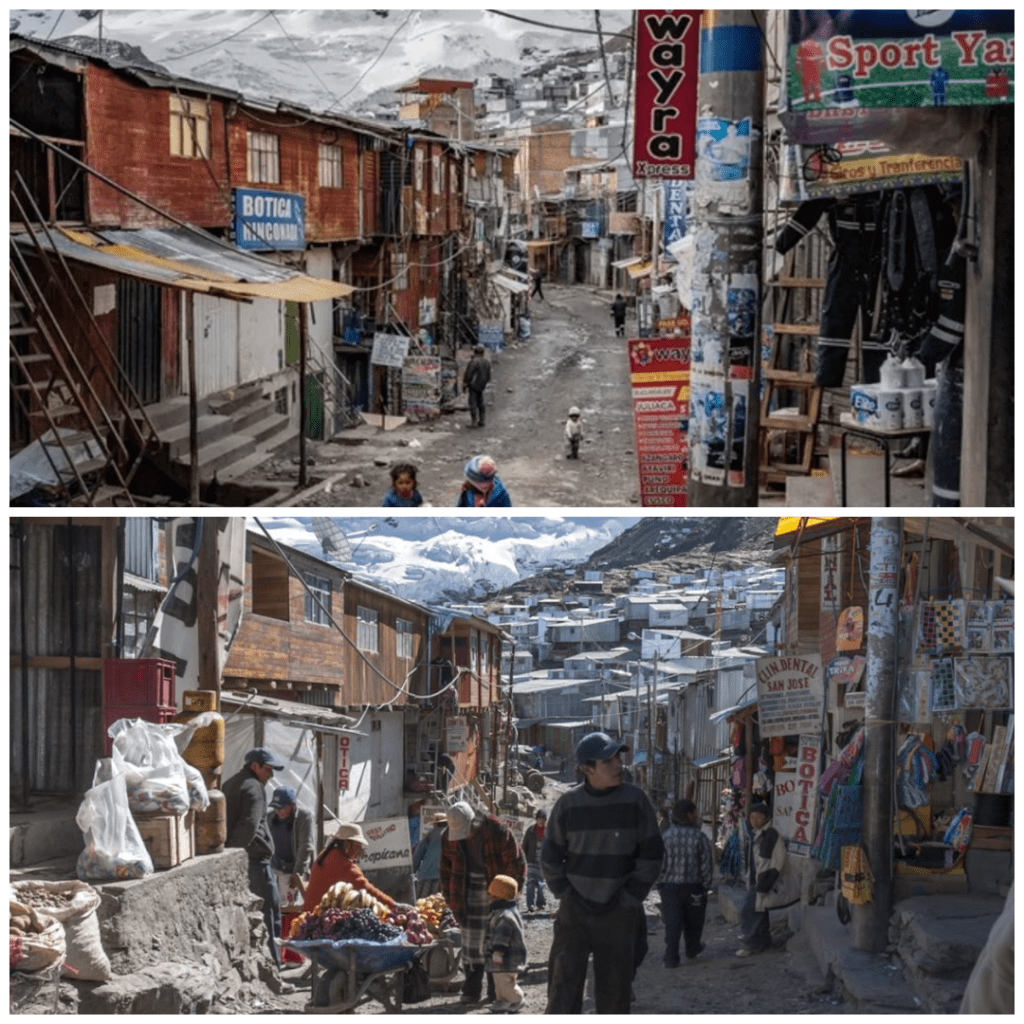

You approach the town from a long, winding dirt road. There’s no water system, no sewage lines, garbage collection is non‑existent. You see wooden shacks where miners live, and textile stalls run by women trying to make a living. And just above it all looms “La Bella Durmiente” glacier, the Sleeping Beauty, now receding and melting, casting a silent shadow over daily life.

Inside the labyrinth of steep paths and narrow alleys, people live by gold. Men enter mines deep into the mountain wearing little protective gear, breaking rock, hauling sacks. The system is called “cachorreo.” They dig and sift on hope—sometimes they find enough gold to walk away with a life‑changing amount; other times they end the month with nothing. Women sift through waste rock dumped outside the mines, hoping to find flecks left behind.

I met Josmell, a miner in his early 30s. He began working at twelve because his family needed the money. He’s tough, lean, quiet, a guy who stands at the mouth of a mine shaft at dawn, waiting for daylight to fill the gray world above. He laughed when he told me gold is easier to find than clean air. Respiratory illness is part of daily life. They cough, they wheeze. Doctors aren’t here. Waiting for medical help means heading down several hours of treacherous road.

Still, there’s a strange resilience here. Every home—some no more than plank walls held together by hope—tries to keep warm. People burn alpaca dung to heat their rooms, and solar panels or Trombe walls bring a little comfort to those who’ve received aid. I visited one home lined with solar panels, floors of wood laid down by volunteers. The temperature inside rose by 15 degrees—still cold, but survivable.

Kids go to school here too. There’s a teacher appointed by the government who makes a long trek each week to reach students in tiny villages even higher up. In Japura, another 14,000‑foot community, volunteers recently installed wood floors and brick stoves, bringing warmth and comfort to families that barely scraped by.

Living at this height changes everything. Sleep comes in disjointed fits because your body is starved for oxygen. Walking uphill feels like breathing through a straw. Silver, copper, lead—all piled on top of human costs. And still, families are born, kids grow, people laugh and cry and hold hands.

There’s no romantic mist here, no Instagram filters. Rain falls, snow melts into slush, and mining carts rattle down cobbled paths filled with litter. The town is chaotic, messy, and brutal—and that’s precisely what gives it life. People build homes on unstable slopes. Children chase chickens. Vendors sell bread in plastic bags. Every day is a battle against the elements, but every night they gather in kitchens, share stories, eat hot stew, and hope for gold dust in their pans the next day.

The environment also shapes community. Folks share food and blankets. They celebrate Carnaval here, too, though their masks and costumes have a DIY, homemade feel. Music echoes off the mountain walls—but there’s no grand plaza or stage. Some nights, a guitar strums echoes of homesick tunes. I remember one man, voice low, singing of the valley far below, of fields and river water—and for a moment I saw tears in his eyes. He missed green things.

Outsiders rarely visit. Tourists can’t breathe this high without risking serious altitude sickness. But journalists from outlets like Science magazine, National Geographic, and The New Yorker have come here to report the stark, raw truth. They document stories of contaminated water, illegal mining, violence, even short life expectancies—some say average lifespan can be as low as 35 in this highest‑altitude city. It’s not a place of clichés. It’s a place of extremes.

And yet, you can’t say it’s bleak. People live here because they believe in transformation. In finding gold. In sending their children away from poverty. They build. They hope. They stay.

When I left La Rinconada, I understood more than I ever had about what it means to survive. To live in the thin air. To dream big in a place most of us would run from. Standing at that altitude, I thought about oxygen, about desperation, about perseverance. I thought about the courage it takes to raise a child where snow could fall any minute. Where air is borrowed, not guaranteed.

I carry that memory—the sound of wind hitting tin roofs at night, the laughter of kids gathering stones to play, the sight of miners covered in gold dust, eyes bright with hope. It’s a memory that won’t leave me. It’s not a postcard. It’s a heartbeat.

Because at 16,700 feet, life isn’t measured in convenience or comfort or calm. It’s measured in breaths, in small victories, in the sweat that steams in the cold. It’s measured in families that stay, in homes built from scrap, in dignity carved from rock dust and frost. And in the end, I’d rather remember the people of La Rinconada—not as victims, but as the boldest, most alive souls I’ve ever met.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.

z4w9m6

wj1ja5

twv00o

tfkm1t

xu9bcm

g5vp44

8kgj1v

i96ylq

e6vhsl

6fz6h6

vy8zmo

5pqypb

sklxlf

vlq7nw

a3b9x0

uuyvtb

bct43o

5okd9a

34rvf8

h5ojbk

9zctc6

243saz

c85n99

Gam88 pops up now and again. I’m always looking for a decent payout – who isn’t? It is certainly worth checking it out!. Check them out here: Gam88.

nvrlp7

ilt4hb