How People Survive in the Driest Place on Earth — Inside Chile’s Atacama Desert, Where Some Areas Went Without Rain for Over 400 Years

There’s a place in northern Chile that changes how you think about “dry.” Imagine a stretch of land where rain hasn’t fallen in centuries—where even seasoned travelers pause before calling it a desert. That’s the Atacama Desert, the driest non-polar desert on Earth. Some weather stations there haven’t measured rain since the 1500s. It’s a place where silence is so thick you can taste it on your tongue—and where life, against all odds, finds a way.

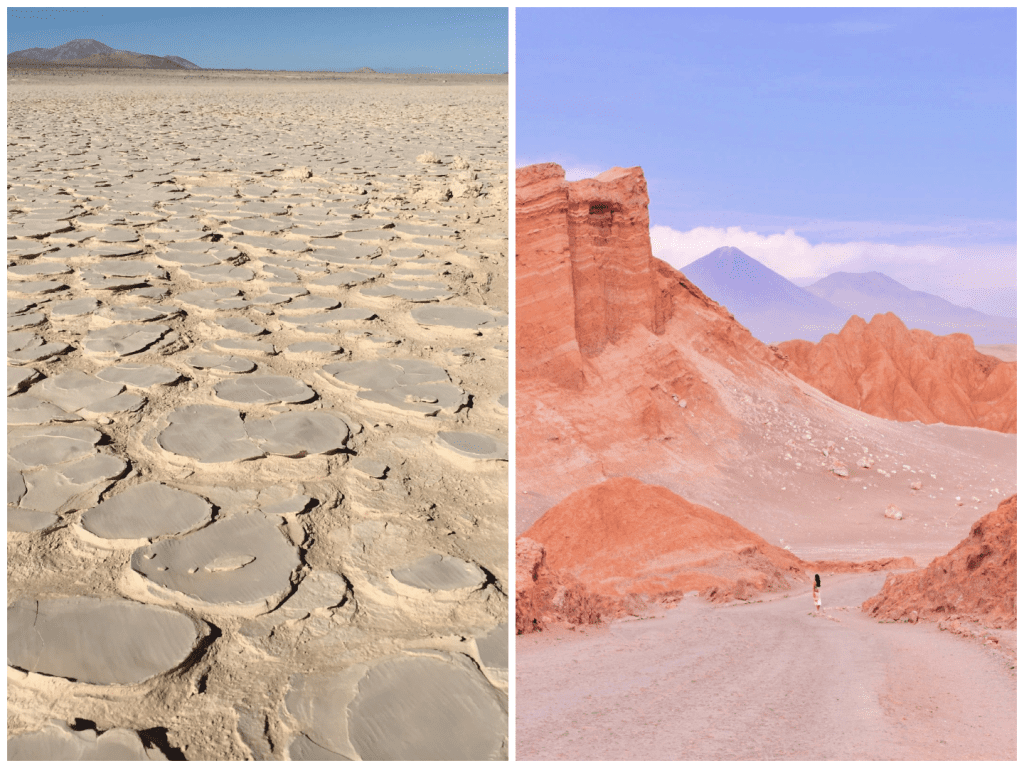

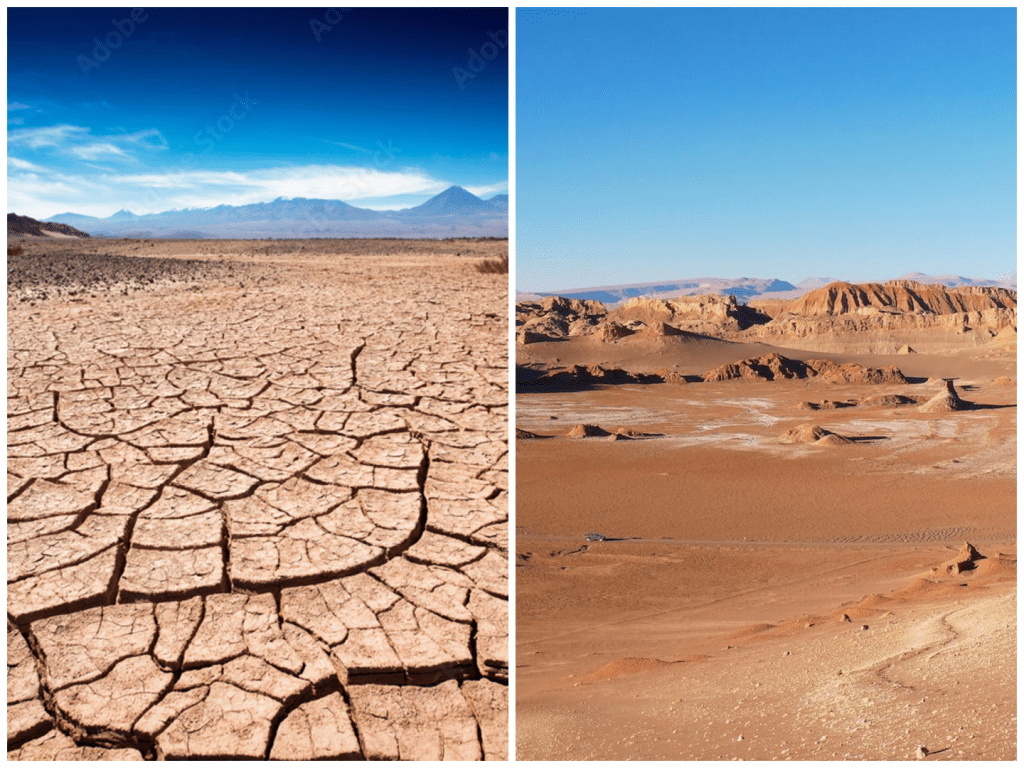

Growing up, I’d heard that the Atacama was like walking on Mars—red, rocky, barren. But learning that some spots went 400 years without a raindrop made it feel almost alien. I pictured cracked earth under a white sun, and I wondered how anything could survive. Yet, people do. And they’re doing more than surviving—they’ve found ways to live, and even thrive, in this near-lifeless land.

How Do You Survive Where Rain Doesn’t Fall?

First, let’s get a sense of why it’s so dry. The Atacama sits between two natural walls: the Andes Mountains and the Chilean Coast Range. Moist air from the Pacific hits those walls and just… dies. Plus, the cold Humboldt Current offshore blocks moisture from forming rain clouds. The result? Many areas get less than 1 millimeter of rain a year—sometimes none for centuries.

When occasional rains did come in 1971 or during El Niño, the desert erupted into color. Wildflowers blanketed the hills—an epic transformation. But decades often pass between those events, and then it’s back to the empty hush.

Yet life endures. Beneath the surface, microbes cling to moisture in rock cracks. Some ancient Andean communities built agriculture thanks to hidden water from snowmelt. This sparse but steady existence is thanks to an unlikely ally: fog.

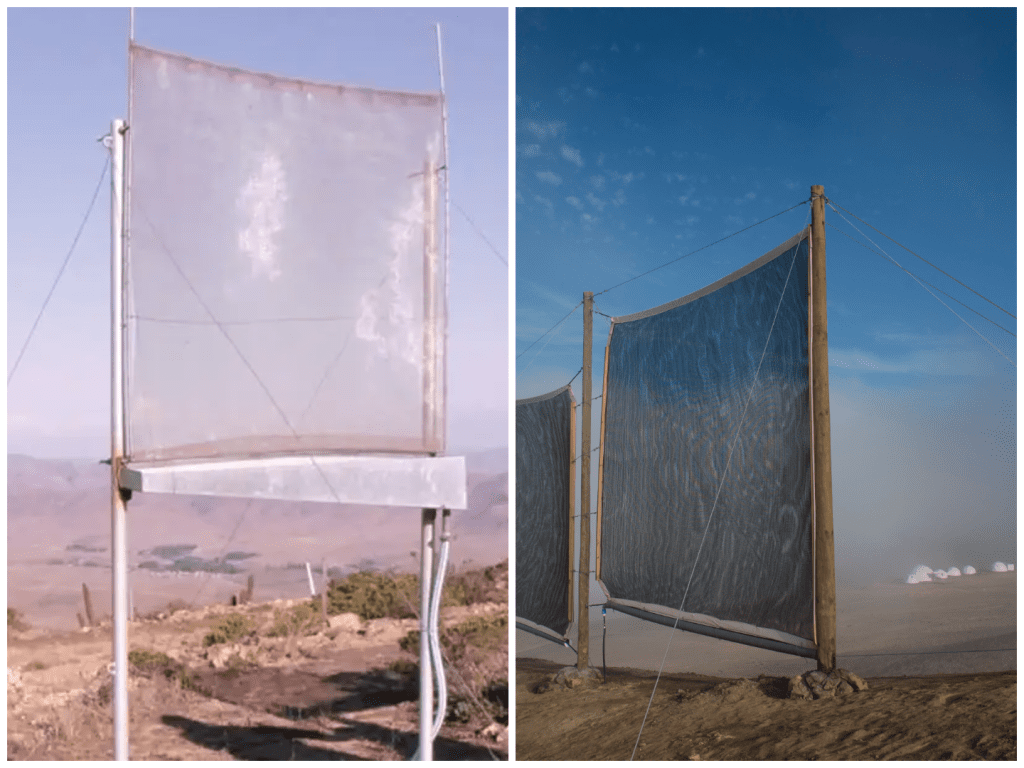

Locals call it camanchaca, a mist rolling off the Pacific. It doesn’t bring rain, but the moisture in it is enough for specially adapted mosses, lichens—and even humans—to survive. They harvest it with nets, capturing water literally out of thin air. Modern techniques even let them grow lettuce and lemons under mesh farms using only fog water. In this desert, people don’t just take—they innovate.

Living in a Place That Feels Otherworldly

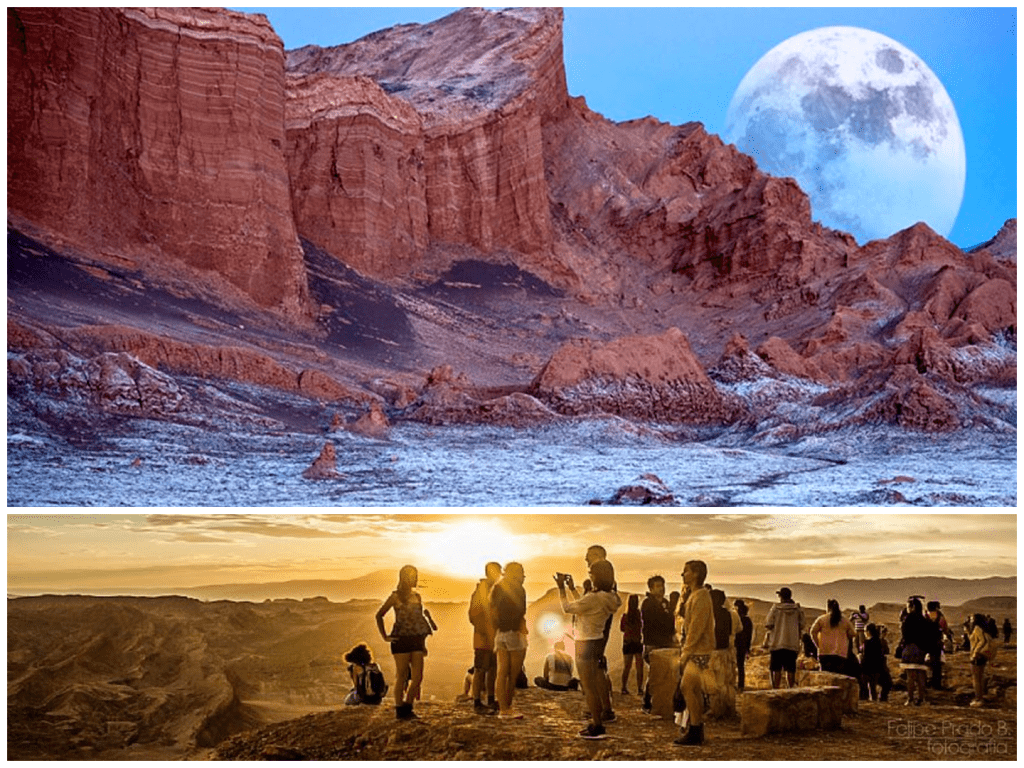

Travelers who reach Valle de la Luna—Valley of the Moon—often say they’ve been transported to another planet. Imagine jagged rock formations shifting in orange light, wind-sculpted dunes, salt flats shimmering in the midday glare. No birdsong, no water noise—only wind and the crunch of your boots on alien ground. At night, the sky opens up. With no light pollution, the Milky Way blazes across velvet darkness.

It’s why NASA tests Mars rovers here. Scientists even studied whether adding water might kill microbes adapted to extreme dryness—an astrobiology lesson from Earth to Mars. It’s both a living lab and a lonely marvel.

That loneness can feel powerful. Locals talk about silence not as emptiness but as space—space to hear your own thoughts. Indigenous Atacameño communities have lived here for centuries, herding llamas and mining salt, adapting their lives to the driest place on Earth. Even small oases fueled by underground water or camanchaca provide life—and community—in this stark world.

Why the Atacama Still Matters Today

The Atacama isn’t just a curiosity on a map. It’s a mirror. It reminds us how fragile the line between life and death can be, how adaptability matters, and how innovation starts sometimes with scraping water from fog.

As climate change worsens elsewhere, and global dry zones expand, the fog harvesting techniques pioneered here become valuable solutions. It’s not just about surviving the driest place on Earth—it’s about applying those lessons everywhere.

The recent wildflower blooms? They remind us that change can be sudden—and beautiful. The silence shows us how rare life can be. The stars show us how small we are—and how wide the universe feels. In that stillness, there’s comfort and wonder.

If you ever find yourself planning a trip to Chile, make your way to the Atacama. Stand on the valley floor at sunrise. Pebble in hand, listen to nothing but your breath. Watch how fog creeps over cactus tops. See how communities have turned scarcity into strength.

Because this place teaches more than geography. It teaches perspective. That even in the driest place on Earth, life persists. Sometimes hidden. Sometimes fragile. Always remarkable.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.