Deep in the Peruvian Amazon, One Mysterious River Reaches 200 °F—And the People Who Live Beside It Say It’s Alive

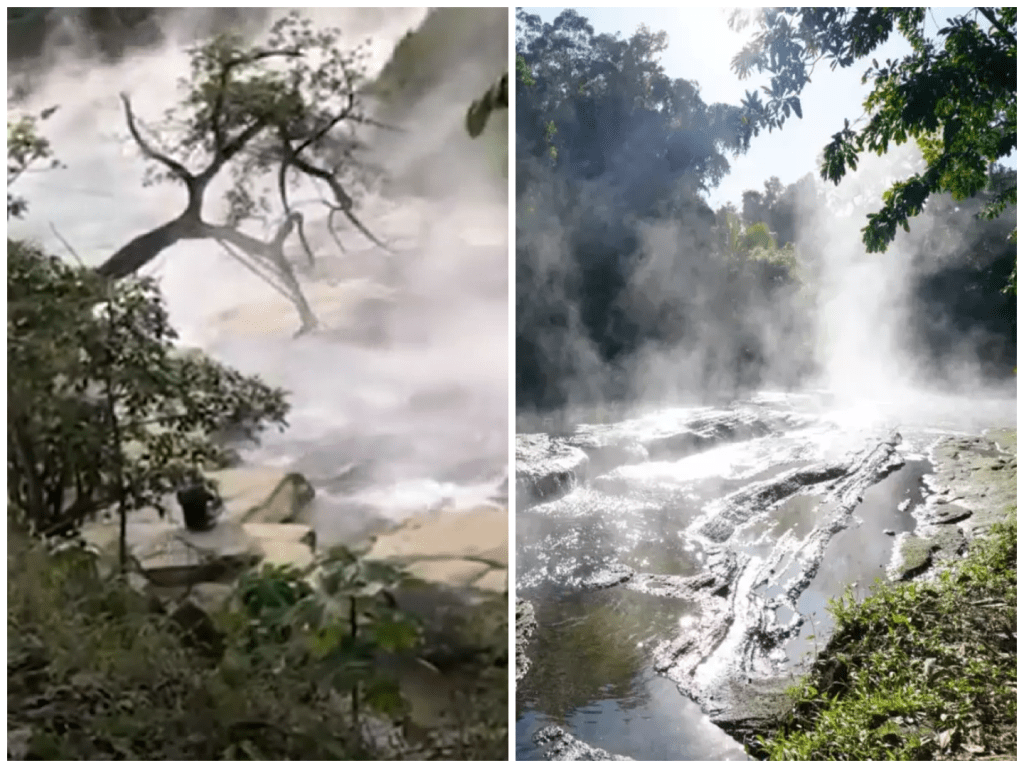

I still remember the moment the forest opened and I first saw steam rising above the canopy like smoke from an invisible fire. We had walked for hours—canoe, mud path, and hanging bridges—until the air smelled faintly of sulfur and wet leaves. Then the trees parted and there it was: the Shanay-Timpishka, the “Boiling River.” From a distance it looked calm, the water tea-brown and slow, but up close it hissed and popped. Little whirlpools spat droplets that sizzled when they touched the leaves. The banks were white with minerals left behind by scalding spray. Local Asháninka people call it the child of Yacumama, the great serpent spirit that mothers all waters. They are not exaggerating. Touch this river for longer than a heartbeat and it will peel skin like fruit. Temperatures along the hottest stretches flirt with the boiling point of water, high enough to brew coffee or cook an unwary toad that slips from the bank.

The river, hidden deep in Peru’s Huánuco region, flows for only about four miles, yet it commands respect that larger waterways never earn. Legend says it once punished a greedy gold seeker by boiling him alive. Geologists say rainwater seeps deep into fault lines, heats far underground, and rushes back through cracks in the riverbed. No active volcano stands within hundreds of miles, yet the water is a liquid furnace, rising as a thin ribbon of steam-crowned wonder in one of the world’s wettest forests.

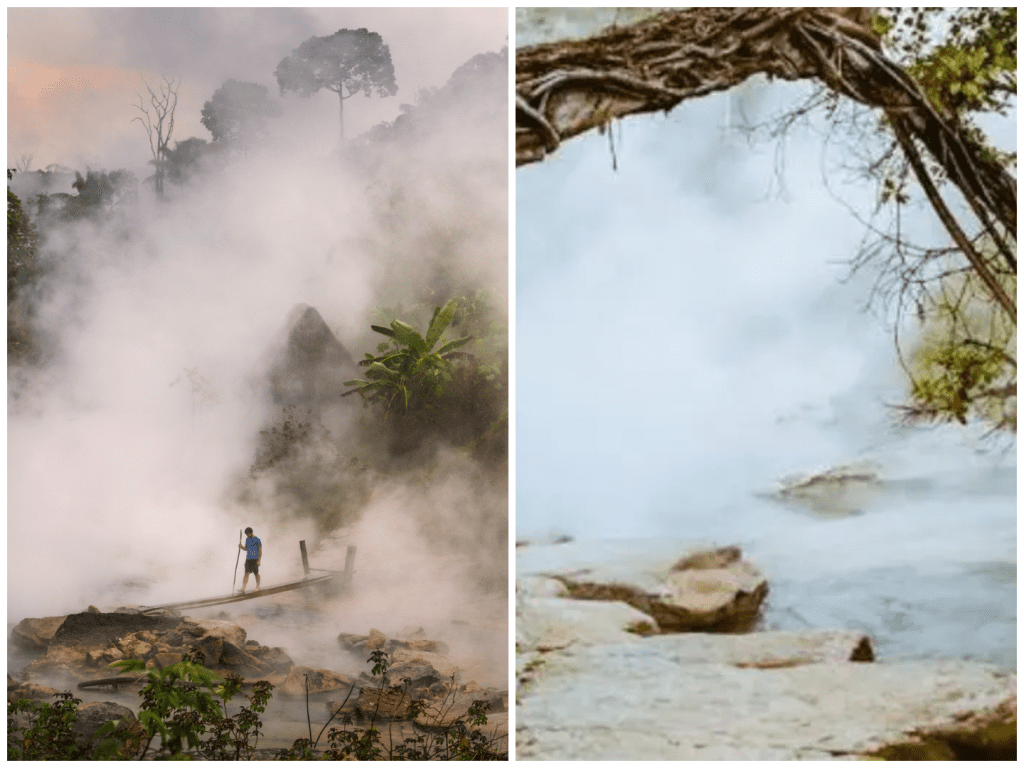

Peruvian-Nicaraguan geoscientist Andrés Ruzo heard his grandfather’s stories and set out in 2011 to prove—or debunk—the myth. He expected exaggeration. Instead, his thermometer read 95 °C, 96 °C, 97 °C. In a Ted Talk watched by millions, he confessed he nearly fainted from the humidity and the shock of realizing the legend was real. Maps had missed the river; scientific papers barely mentioned it. The jungle had kept a furious secret.

I had watched that talk from an air-conditioned room and felt a shiver of disbelief. In person, disbelief vanishes quickly. The first wave of moist, sulfur-tinged air blurs the rational mind. Leaves curl to ash on contact. The air hums with hidden power.

Heat, Myth, and Survival

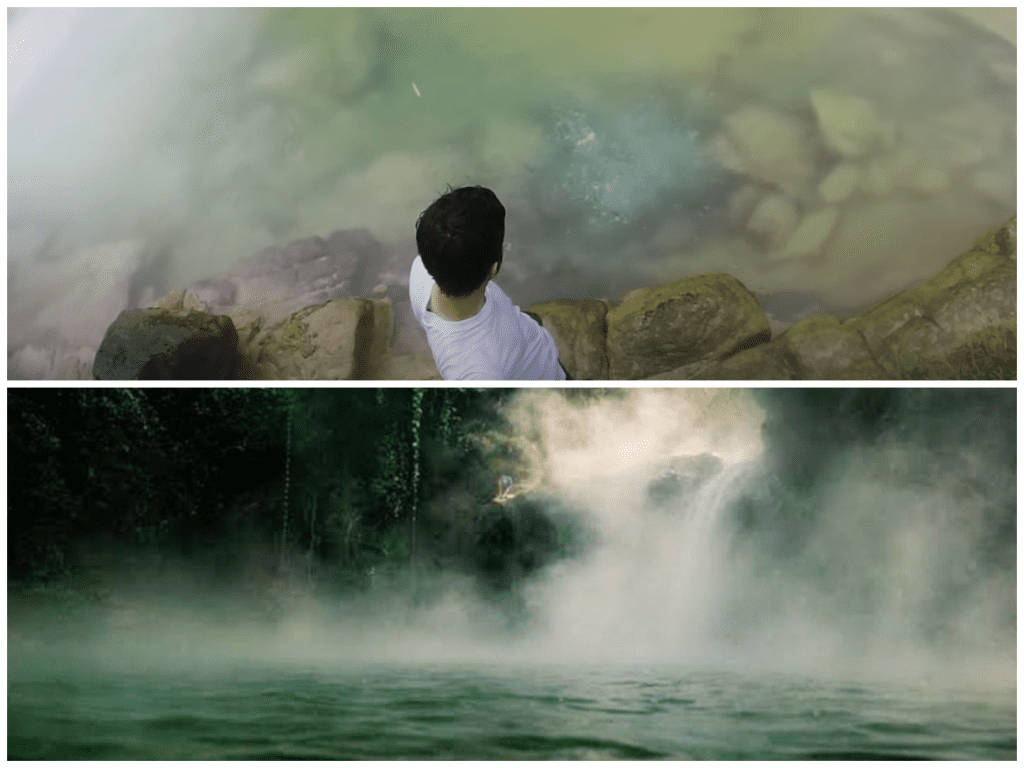

People do live here. High on the bank where the hot river meets a cooler side stream, a healing center called Mayantuyacu hums softly beneath palm roofs. Shamans guide visitors through plant ceremonies while steam drifts past wooden porches. They treat the boiling water with reverence, gathering stones too hot to touch, plunging them into medicinal baths that hiss as though the forest itself is exhaling.

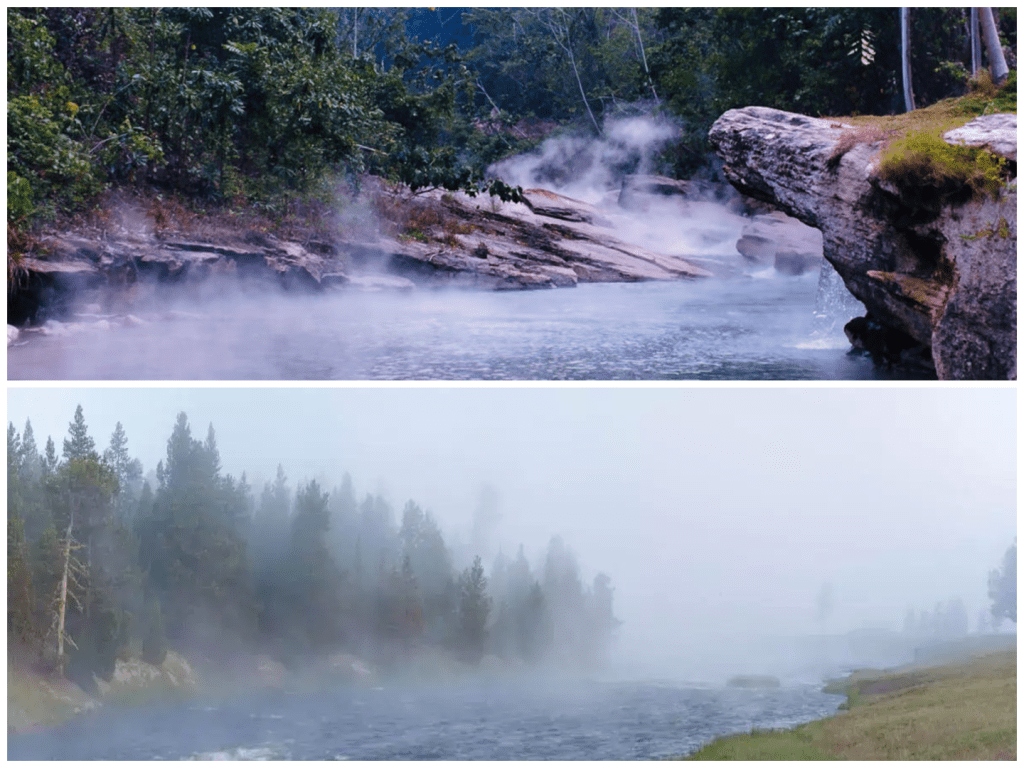

Numbers tell one story: six-and-a-half kilometers of thermal channel, water roughly thirty meters wide in places, depths plunging fifteen feet or more, average temperature in the nineties Celsius. Tradition tells another: the river breathes, listens, and punishes arrogance. Both versions coexist without argument.

At dawn, a local guide named José led me along the bank. He tapped ahead with a long stick, reading the ground like Braille. Mist wrapped the forest so thick we barely saw ten steps ahead. José pointed to a place where tourists once ignored warnings; he claimed the rubber soles from a lost sandal remain fused to rock. “The river hears pride,” he whispered, as though the water might eavesdrop.

Later that morning I met a biologist collecting extremophile microbes that thrive in near-boiling water. She used metal tongs to lower glass vials, shoulders tensed from radiant heat. “These organisms might help us design new antibiotics,” she said, sealing the vials in a cooler packed with ice flown in from Pucallpa. Here, danger and discovery share the same channel.

Scientists continue to debate the exact mechanics. The prevailing theory involves a deep crustal fault that functions like a natural boiler: rainwater travels down, is heated by Earth’s internal warmth, then returns through fractures beneath the river. The absence of volcanic rock nearby adds to the mystery. Yet the river’s power is undeniable. Small mammals that fall in rarely climb out. Guides showed me bleached bones at the hottest bend—a natural warning in stark white.

Why the Boiling River Matters

Standing beside water hot enough to kill forces a shift in perspective. We like to imagine every corner of Earth mapped and measured. Yet this river remained largely unknown to science until the twenty-first century, protected by remoteness, thick forest, and local silence. Satellites missed it because constant steam looks like low cloud. Government surveys ignored it because no lucrative mineral lay beneath. The river endured as a story, passed around firesides, waiting for someone curious—and respectful—enough to listen.

That secrecy is threatened now. Illegal loggers creep closer; land speculators eye the rising value of jungle soil; mercury from distant gold mines rides downstream. Andrés Ruzo’s Boiling River Project partners with Asháninka guardians to build a protective buffer: only guided visits, no plastic bottles, no soap, no souvenirs chipped from river stone. At night, solar lanterns cast gentle halos over wooden walkways while the river hisses beyond the treeline, invisible but loud, like a kettle that never cools.

As I packed to leave, José asked me what I would tell people back home. I answered honestly: I’d speak of the heat, the danger, but mostly the respect. Respect for a place where myth and measurement overlay perfectly, where indigenous knowledge led modern science to discovery instead of the other way around, where a river can scorch the careless yet nurture microbes that may one day save lives. José nodded. “Tell them,” he said, “the river has a heart, and it beats hot.”

Back aboard the canoe drifting toward the cooler Pachitea, I glanced over my shoulder. Steam still curled above the canopy; morning sun caught it and turned it gold against endless green. In that moment I realized the planet still holds wonders that slip through satellite lenses and academic papers—wonders that demand sweat, humility, and a willingness to believe a grandfather’s story.

The Shanay-Timpishka boils on, doing what it has likely done for centuries, untouched by pipelines, unmastered by dam walls, unclaimed by tourist brochures. It is a reminder that Earth’s strangest miracles often hide in the places we deem too remote, too inconvenient, too mythical to matter. And it is a promise that if we listen—truly listen—the land still has stories that can make even the most comfortable traveler break a sweat of awe.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.