How to Watch Two Meteor Showers Collide on July 29–30 — Southern Delta Aquariids + Alpha Capricornids

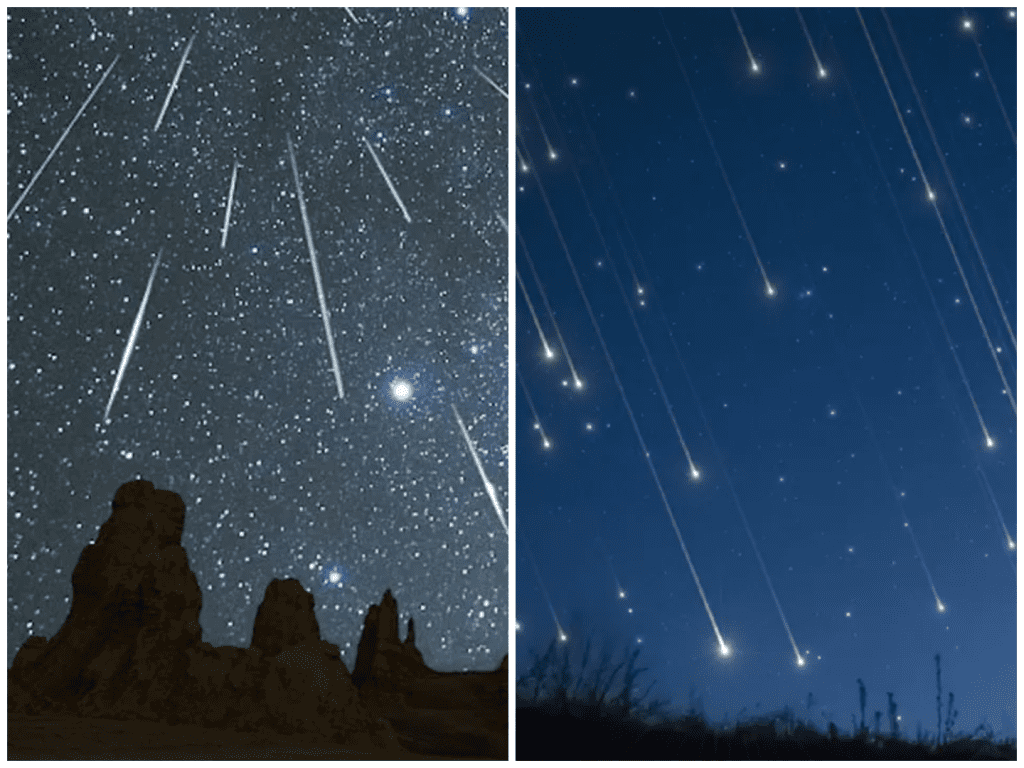

If you have ever waited for a shooting star with your chin tipped up and your breath held, you know that small pause before it finally flashes past. That pause will feel different this week. Two separate meteor showers are set to crest on the same night, and the sky will offer a long, unhurried performance rather than a quick burst. The Southern Delta Aquariids and the Alpha Capricornids reach their best activity overnight on July 29–30, 2025. It is not a storm, but under dark skies you can expect a steady trickle that adds up, with the quiet ones coming often and the brighter ones arriving now and then like a drumbeat.

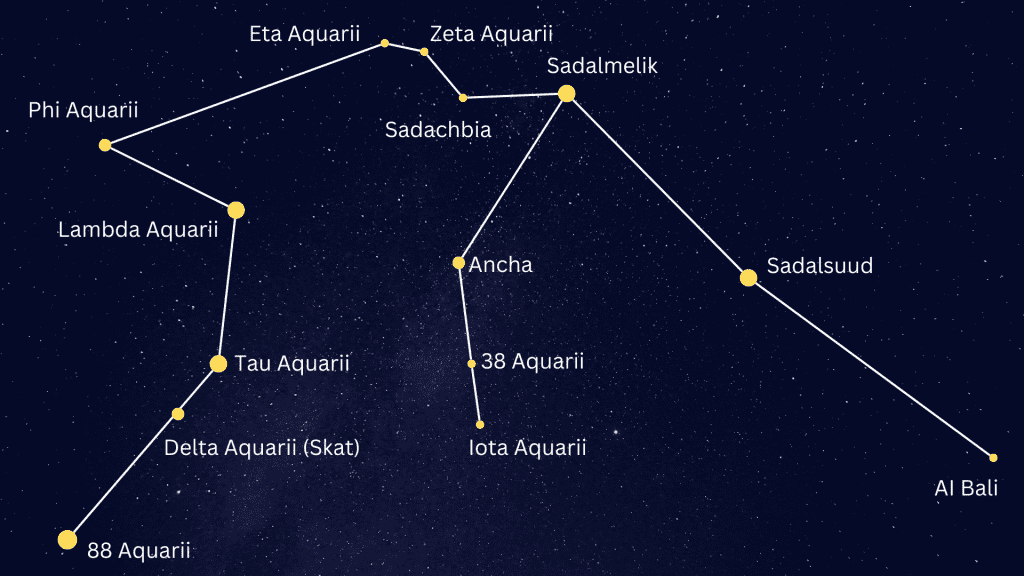

The personalities of the two showers are different, and that is part of the charm. The Southern Delta Aquariids are the workhorses. Their meteors are usually faint and quick, sometimes leaving a thin ghost of light that hangs for a heartbeat after the streak disappears. They come from the dusty trail of Comet 96P/Machholz and tend to be most rewarding in the second half of the night when their radiant in Aquarius climbs. Think of them as the background music of late July: soft, steady, and best appreciated when you give them time. On a good night at a dark site, it is reasonable to see around 15 to 25 of them in an hour.

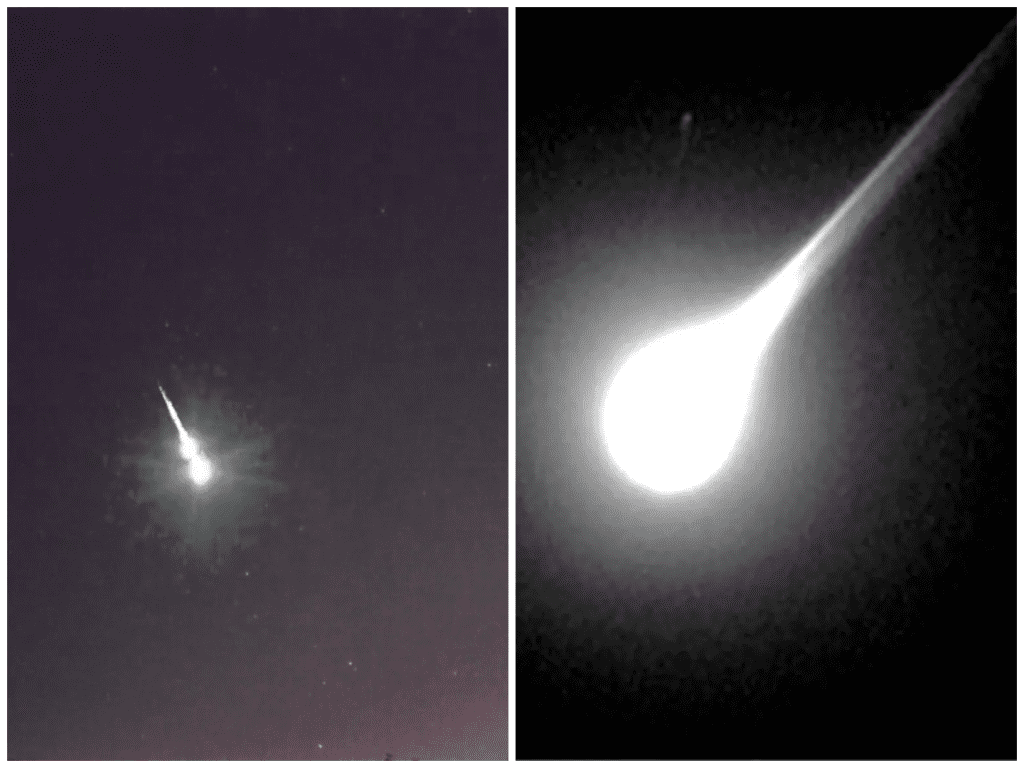

The Alpha Capricornids are few but loud. They come from the debris of Comet 169P/NEAT and are famous for slow, bright fireballs that can turn even a casual bystander into a sky fan. Their hourly rates at maximum are usually just a handful, but many observers would trade a dozen faint streaks for one golden ember that seems to float. When the two showers overlap, the effect is special. The Delta Aquariids fill the gaps with fine strokes while the Alpha Capricornids throw in the occasional underline.

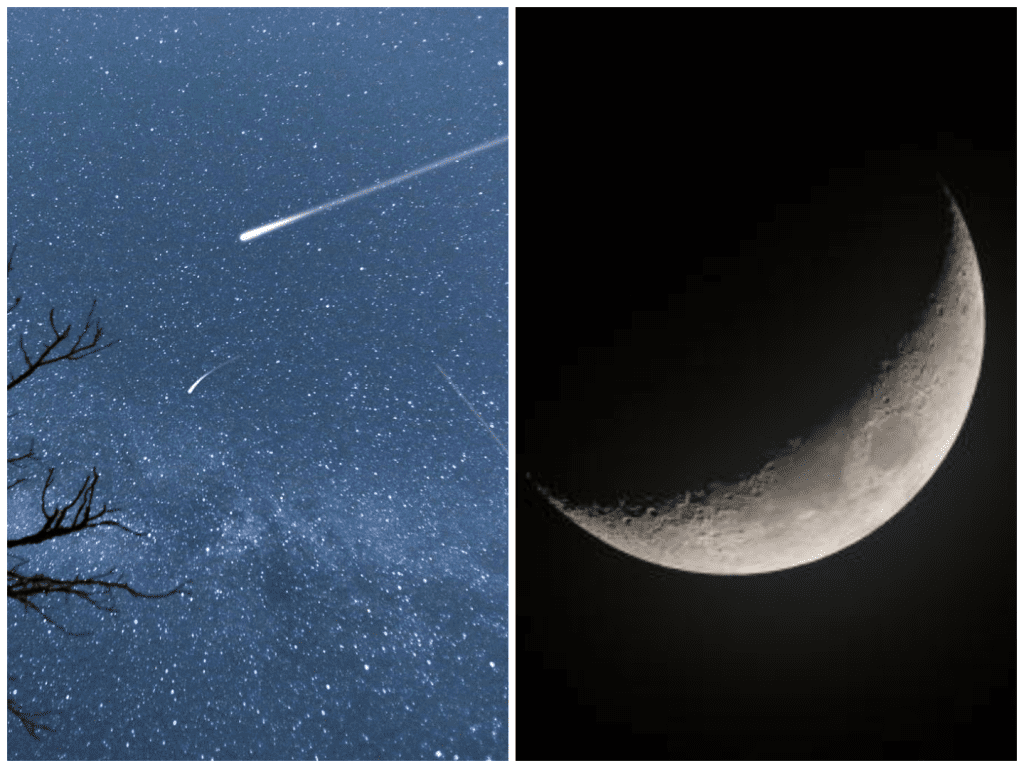

The timing is kind this year. The moon will be a waxing crescent and will set early, leaving the late night and the hours before dawn nice and dark. That matters because the Delta Aquariids are subtle. City glow eats them whole. A small crescent is friendly; it gets out of the way and lets your eyes adjust. If you can give yourself twenty or thirty minutes with no phone and no bright lights, you will start to notice the fainter ones too. It is a reminder that a lot of skywatching is simply patience and comfort. Take a chair you can lean back in, a light layer even if the day was hot, and a drink you like. Let the night do what it does.

You do not need star charts to enjoy this. The basics help, though, because they explain why the night improves as it gets later. The Delta Aquariids seem to fan out from Aquarius near the star Skat (Delta Aquarii), and the Alpha Capricornids from Capricornus. For many in the Northern Hemisphere both radiants sit low in the southern sky early in the night and ride higher toward dawn. In the Southern Hemisphere they climb higher still, which is why reports from the southern tropics often sound happier. No matter where you are, a wide view is your friend. The biggest mistake is looking at one small patch. Spread your gaze and let motion pull your attention where it needs to go.

Be ready for clumps and lulls. Meteors are not polite or even. You might get three in thirty seconds and then nothing for ten minutes. That is normal. Earth is moving through dusty streams that are not uniform. Sometimes we pass a slightly thicker ripple, and sometimes we cross thin air. If you find yourself getting impatient, soften your eyes, put your phone face down, and listen to the night for a while. Meteors love to arrive right when you think about leaving.

If you are watching from Pakistan (Asia/Karachi time), the sweet spot is the predawn window on Wednesday, July 30, when both radiants are higher and the crescent moon is long gone. For North America and Europe, the same rule applies: after midnight toward dawn is best, with the last two hours before twilight often the richest. The showers are active for days on either side of the date, so if clouds win one night, try the next. A handful of the year’s nicest meteors show up when you were not planning to see anything at all.

It is also fun to understand what your eyes are translating. The Aquariids are medium speed, hitting the atmosphere at roughly forty kilometers per second, which helps explain their quick lines and delicate trains. The Capricornids are slow by meteor standards, around the low twenties in kilometers per second, which gives them that fireball grace note. Those numbers will not make you catch more meteors, but they do make the show feel more alive. Space dust is not just light; it is motion and heat and old comet tails turning into brief stories.

This night is not meant to compete with the August Perseids. Those are the headliners with higher counts under dark skies. This is different. It is a duet. It is two old debris streams sharing the same stage and giving you a reason to be outside for a while. If you live under heavy light pollution, do the simplest thing you can to help yourself: step farther from the brightest blocks, turn your back to the city glow, and shield your eyes from nearby lamps. Even a small improvement in darkness can double how many faint streaks you notice.

If you are choosing a place to go, think about horizons. You do not need a mountain; you want open sky. A beach with the town behind you, a field with trees low on the edges, a rooftop that is not flooded with light. If you drive, pick your spot in daylight if possible and check the rules for parking and park hours. Bring a red light or tape a bit of red film over a small flashlight so you do not blast your own night vision at the first mosquito buzz. Tell someone where you are going and when you will be back, then give yourself time to settle.

There is always a second show going on during a night like this: the quiet things. A night bird calling from a hedge. The way your breath looks when the air cools. The moment when the Milky Way shows itself because your eyes finally gave up on everything except the dark. When a bright Alpha Capricornid ambles across your field of view and leaves a glowing wake, you will feel that small thrill that never gets old. When a faint Aquariid scratches a thin line and is gone, you will catch yourself smiling because you were ready and you saw it. Neither of those moments translates well to a screen. That is the point.

If you want one simple plan, here it is. Pick a spot you trust. Go late. Arrive early enough that you are not still fussing with bags when the best hour arrives. Put your phone away and give your eyes twenty minutes to adjust. Look up, mostly south if you are north of the equator and mostly overhead to north if you are south of it. Count your first ten meteors out loud with a friend or to yourself, just for the fun of it. When the last one surprises you at the edge of your vision, make a wish even if you say you do not believe in that. Wishes are old as dust too.

There is something tender about a night like this. It is not loud and it is not rare. It happens every year, and yet each time feels new because the sky and the weather and your life are not the same as they were last July. The Aquariids and Capricornids keep their slow appointment. The moon bows and leaves the stage. For a few hours your world gets bigger with nothing more than darkness and a little patience. You go home with a stiff neck, maybe a few mosquito bites, and a small collection of lights in your head that will visit you again when you close your eyes. It is enough.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.