The Underground Salt Cathedral of Colombia — A Church Carved Into the Earth

I remember the first time I saw a photo of this cathedral buried deep inside a mountain of salt—it looked surreal, like something from a dream. The columns, the glowing cross, the soft lights dancing off salt walls two hundred meters underground near Zipaquirá, Colombia. It pulled at my imagination and made me wonder how someone even thought of building a church in a salt mine.

Salt in that region goes back hundreds of millions of years, formed from an inland sea that evaporated long ago. Generations of Muisca people, known as the Salt People, mined it as far back as 500 BCE. Salt from Zipaquirá even helped fund South America’s wars of independence in the early 1800s. No surprise they once called it the “City of Whites.”

The earliest chapel in the mine dates to around 1932, where miners carved out a small sanctuary to pray before they began their shifts. It was a humble space with crude salt crosses and hope for safety below ground. That small gesture grew into something grander in 1954 when they opened the first full Underground Salt Cathedral. It had three naves, huge columns, and a giant salt cross that cast a shadow above the main altar. It became a pilgrimage site, a place of wonder and faith in the depths.

But nature can be fragile. That original cathedral was carved within an active mine with shifting tunnels overhead, and in 1992 it was closed due to safety concerns. Yet creative minds prevailed. A new cathedral was constructed a little deeper in the rock—around 180 meters below the surface. In 1995 it opened with renewed design, guided by architect Roswell Garavito Pearl.

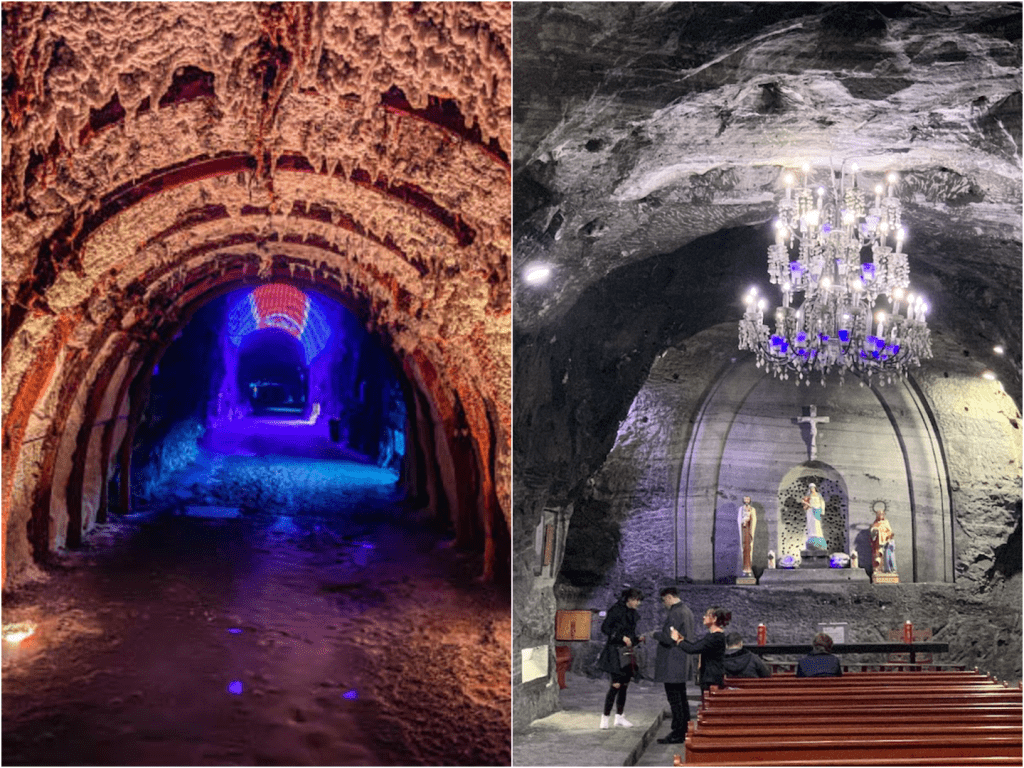

Today, reaching the Underground Salt Cathedral is an experience in itself. You enter Parque de la Sal, a complex built over the mine that includes a brine museum, climbing wall, and scenic grounds. Then you descend via a gently sloping tunnel carved in salt, passing fourteen Stations of the Cross—salt sculptures illuminated in soft golden light. The air is cool, gray, and strangely clean, with the smell of ancient mineral lingering.

At the heart lies the vast main nave, a cavernous space lit in gentle blues and purples. The centerpiece is a towering crucifix carved in salt, rising 16 meters tall. Columns of salt hold the ceiling aloft, and salt-carved sculptures—like replicas of Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” and “Pietà”—watch over the pews. Light seems to waltz across the walls as colors shift. It’s spiritual, serene, and slightly surreal.

Families arrive for weekend masses led by the faithful. About 3,000 people pack the pews each Sunday. For tourists, the cathedral offers audio tours, a 3-D film showing the salt’s origin, and the chance to walk the Miner’s Route—a short peek at the lives of salt miners over centuries. Guides point out pyrite dust veins and trace the contours of ancient marine layers hidden in the stone.

Walking out afterward, I was struck by a feeling of quiet awe. The town of Zipaquirá, 50 km north of Bogotá, with its colonial plaza and balconies, feels cozy and welcoming. Visiting both the town and the salt cathedral makes for a full day—exploring culture above and history below.

Beyond its faith role, the cathedral is an engineering marvel and a tourist gem. Labeled the “Jewel of Modern Architecture” by many, it draws hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Tours vary: some private, some combined with trips to nearby salt mines like Nemocón. That mine has its own salt lake and waterfall carved into halite.

It’s easy to think of places like Machu Picchu or the Amazon when you imagine Colombia. Yet the Salt Cathedral reveals another kind of wonder—one buried deep into the earth, shaped by faith, and built into mineral veins laid down 250 million years ago.

Even the lighting show is part of the story. Warm bulbs highlight salt textures; deeper hues of purple and blue drape the dome above the cross. One visitor described it as a “cathedral carved in the soul of the earth.”

Leaving, I couldn’t stop touching the salt railings. There was warmth in those halite fingers—human hands shaped for devotion. It reminded me how the miners’ prayers beneath the ground gave birth to something lasting and profound.

The story doesn’t end underground. Every Good Friday, the city holds processions along the miner’s path. Drums, candles, and solemn chants lead hearts upward and inward into the rock. For me, the Salt Cathedral feels like a bridge across time—from Muisca traders to modern pilgrims, from natural oceans to manmade faith, from ancient stone to living community.

Next time you plan a trip to Colombia, think of Zipaquirá—not just for picturesque plazas or salty snacks, but for a church that lives beneath the surface. A place where light meets stone, salt meets spirit, and people meet history.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.