How Colombia’s Salt Cathedral Was Carved 600 Feet Underground—and Feels Like Faith and Stone in One

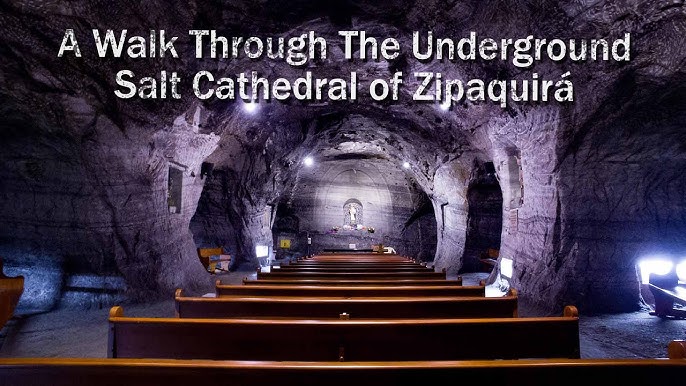

Imagine walking into a mountain. Not hiking up to a cave entrance, but descending into the earth, past pulsing lights, until you find yourself standing in the heart of a mine—and before you, a cathedral. That’s Colombia’s Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, tucked 600 feet underground in an active salt mine, where miners found more than salt—they found sanctuary. It began in the 1930s when workers carved a small chapel into the crystalline walls of the mine. Then, over decades, the vision grew. By the 1990s, a full cathedral stood, larger than life, quiet as a deep breath. The arches and columns, the crosses, the altar—they’re all hewn from salt. The walls sparkle with a soft glow, candles reflect off crystal grains, and the air tastes faintly of earth and mineral. The whole place feels less built than revealed, as if the stone itself shaped the sacred space.

I first heard about it through pictures: a cathedral half lit with blue neon, salt walls that looked alabaster, people kneeling in silence underground. When I visited, I expected theatrical lighting and echoes. What I found was a hush. The kind of hush that makes you lean in. The descent is slow—a long stairway carved in rock, dim lights pointing the way. Then you step into a vast cavern, your footsteps muffled, and your eyes widen. The altar cross stands glowing but not harsh. A low hum of voices, respectful murmurs. It is at once a mine, a church, and a dream, a place where geology and devotion meet.

Carved by Miners, Guided by Faith

The miners were the first caretakers. As they tunneled for salt, they started with a niche in the wall for a candlelit statue. That grew organically—demanding respect, maybe offering hope. Over time, the company and the Church supported its expansion. Architects, artists, and sculptors shaped vaults and corridors. The cathedral spans three naves—the empty, the stations of the cross, and the central chamber with the altar. The salt itself becomes a medium for light. Across the centuries-old rock, grooves in the veins catch light and sparkle. Pilgrims walk the way of the cross, each station hewn into rock, each step deeply tactile and quiet.

And why build a church inside a mine? There’s something both practical and spiritual in it. Practical—miners already spent long hours far underground. A chapel was close at hand. Spiritual—the salt, a humble mineral, becomes holy ground. Salt in Christianity symbolizes purity and preservation. Here, faith rises from layers of earth. People who visit speak of how the cold hush calms the pulse. The texture of the walls, the faint smell of salt in the air, give a sense of being far from noise and distraction. The Cathedral is not about architecture that soars upward—it is about humility that sinks inward.

In 1995, a new, larger version of the cathedral opened in a deeper chamber of the mine, replacing the old one that was no longer safe in active mining areas. The newer cathedral is more symmetrical, more spacious, while still preserving the raw salt walls. The corridors lead visitors through dimly lit paths into vast rooms. Colored lighting—blue, red, warm white—plays on the walls, suggesting sky, earth, and flame. The altar remains carved directly from salt. Some sections feel carved by artists, others as if they were chiseled by water and time. It all feels natural, ancient, and gentle.

A Sanctuary That Reminds Us

Most people visit the cathedral as tourists. Minibuses arrive from Bogotá. Guides speak about salt geology, history, and light effects. People snap selfies. Yet once inside, the cathedral asks for gentleness. The voices drop. Phones go silent. Cameras flash is frowned upon. It asks us to slow down, to listen.

I once sat in that cathedral for what felt like an hour, though it was only twenty minutes. The cathedral corridor emptied, and the ambient sound became the constant drip of unseen water, soft echoing footsteps, and my own breath. The lines of rust‑colored salt and mirror‑like walls faded into a kind of warmth that had nothing to do with light. It felt like spirit.

Afterward, above ground, the desert air tasted sharper. Sunlight felt loud. I realized how rare that silence was—and how easy it is to carry with you once you’ve stood in a place where stone and salt remember stories and faith.

This is why the Salt Cathedral matters—not because it is deep or carved or unique (though it is all those things). It matters because it reminds us what we value: light born from darkness, kindness carved from rock, mystery preserved in a place you find when the world is quiet enough to listen.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.