Inside Cambodia’s Floating Villages: A Life Built on Water and Community

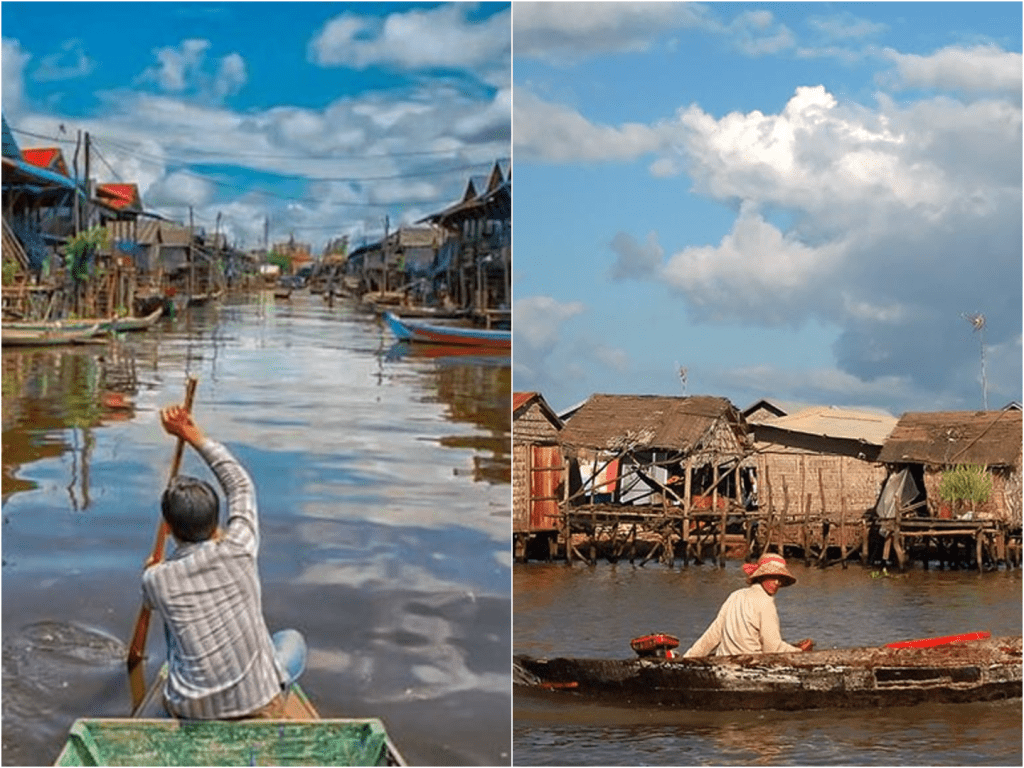

Floating villages on Cambodia’s Tonlé Sap lake feel like stepping into another world, where houses drift gently on water and the rhythm of life follows the tide. I’ll never forget my first glimpse of Chong Khneas, one of the closest villages to Siem Reap. Boats cluster together like long-lost boats returning home, and stilted houses rise from the water, their foundations stretching up to 10 meters on stilts during the dry season. It’s a surreal scene, but it’s also a way of life rooted in resilience and simplicity.

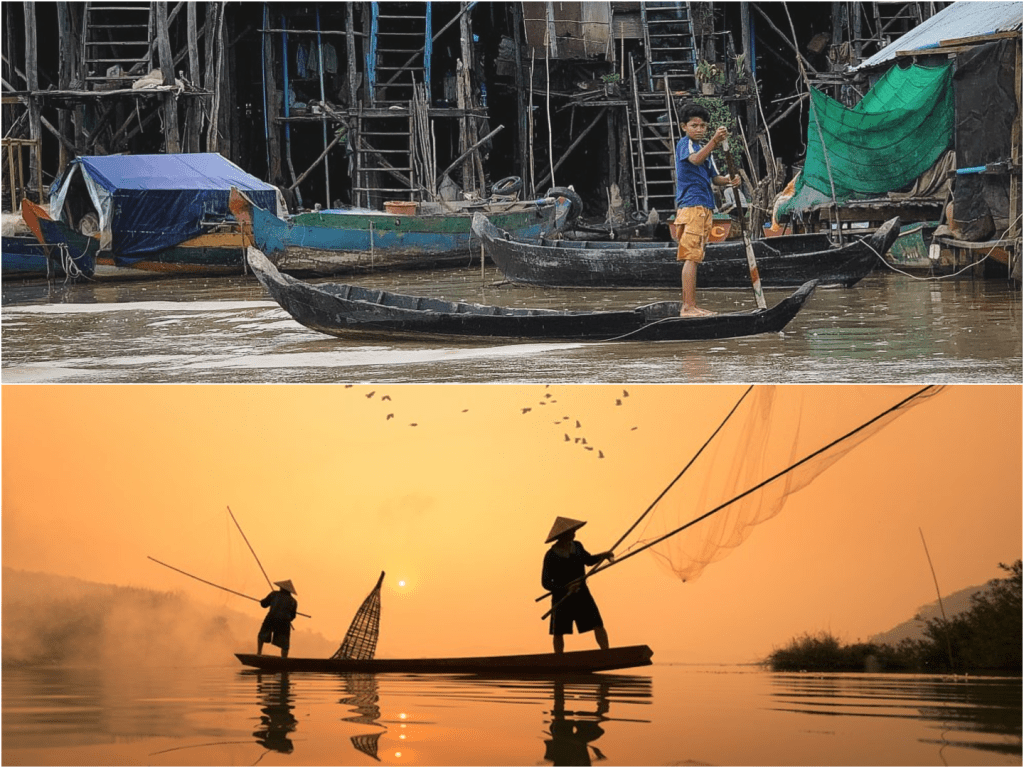

Tonlé Sap is Southeast Asia’s largest freshwater lake, expanding from around 2,500 square kilometers in the dry season to nearly 16,000 square kilometers during monsoon floods. The shifting water defines everything here. Houses float or perch on tall stilts, boats replace cars, and communities adapt to water levels that rise and fall by as much as 10 meters each year. Children learn to navigate the world by boat before they can walk. It felt poetic and humbling to watch them—grouped four or five to a sampan—row themselves home after school, laughing and free as the lake around them.

I spent a morning in Kampong Phluk, waking as the first light kissed the wooden planks. I stepped onto a narrow boardwalk and met villagers who greeted me with calm smiles. They told me nearly all of them fish or farm—floating gardens tethered alongside their homes produce vegetables, and some families even rear fish in bamboo pens. The lake is life here, but that life is feeling its limits. Fishermen like Em Phat have seen fish disappear, forced by climate change and upstream dams. Now, some are farming eels in tanks on land just to survive.

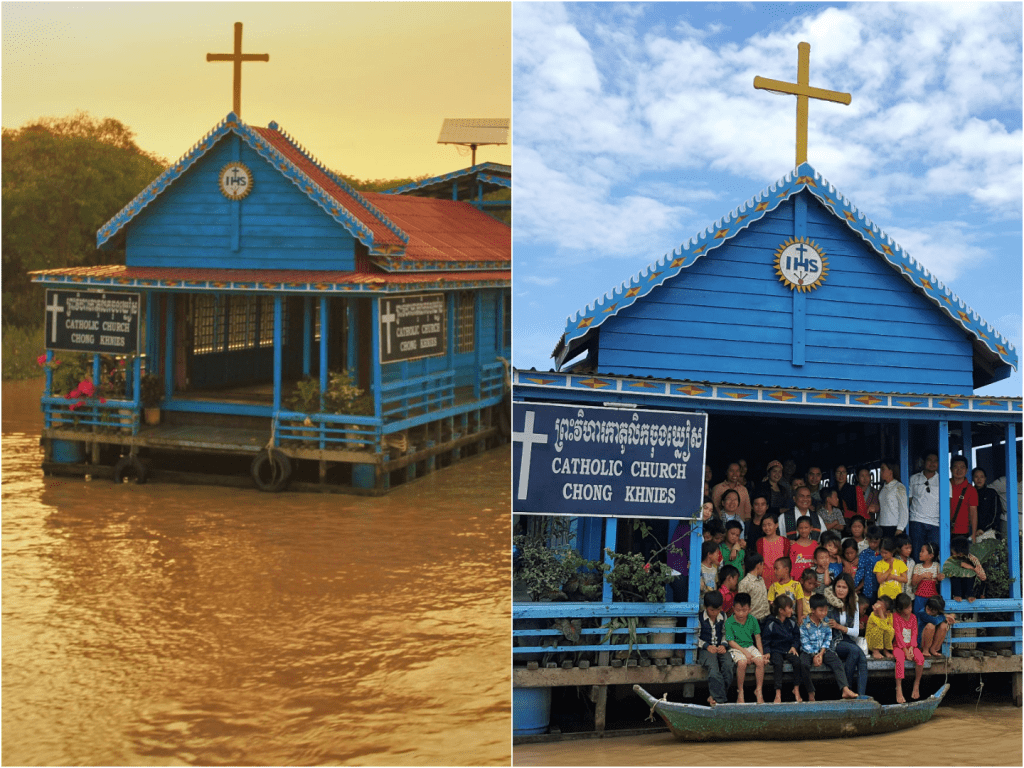

Still, the community is vibrant. Schools float too: wooden classrooms drift beside homes, letting children learn without leaving the water. Markets appear by boat—vegetables, fish, snacks sold from sampans where money exchanges hands with laughter echoing across the lake. I saw a floating church at Chong Khneas, the little white boat-shaped building bobbing quietly nearby, a spiritual anchor in a world of flow.

Floating villages aren’t isolated curiosities. Tonlé Sap sustains nearly three million people in and around its shores, with around 80,000 living directly on the water across some 170 villages. That’s nearly 60 percent of Cambodia’s freshwater fish catch coming from this lake alone. For centuries, this lake powered the rise of Angkor. Today, it remains a vital ecosystem—though it’s threatened by deforestation, infrastructure, and overfishing.

One rainy afternoon, I rode past Prek Toal, a village nestled against flooded forest. Monks floated by in boats and children waved from plank porches. The rising water surrounded houses with tangled roots and green canopies. A boat passed selling ice boxes—frozen treats for kids who darted in and out of homes. It felt like a living painting, ancient and new all at once.

Floating life is shaped by seasons, floods, harvests, and the slow decay of wooden boards. When the water rises, villagers pull their homes closer to trees or tie them together into floating communities. When the water drops, ladder-stepped stilts hold the homes high, and people move closer to essential supply docks on land. It’s a dance with nature, and they’ve learned its steps through generations.

Yet, not everything floats gently. In Kampong Chhnang Province, the government dismantled the last floating village in 2022 to “beautify” the riverfront. Families—many ethnic Vietnamese without proper documents—were relocated to resettlement areas lacking water or toilets. “On the water, we could fish, make a living, move easily,” one woman said. “Here, it gets flooded when it rains, and we can’t go anywhere.” It reminded me how fragile these traditions are, overshadowed by development, identity, and human rights.

But as I left the water behind, I carried something more enduring: a vision of a community living with nature rather than against it. During Bon Om Touk, the Cambodian Water Festival, villagers race boats, float lanterns, and give thanks to the lake and river goddess for her gifts. For them, water is more than survival—it’s spiritual sustenance.

The world could borrow a page from these floating villages: adaptability, respect for nature, community resilience. In a fast-changing climate, with rising seas and threatened ecosystems, the wisdom of living lightly on the land—and water—matters more than ever.

I left Cambodia clutching a small wooden sampan toy, carved by a villager who smiled and said, “Take it, so you remember.” Every morning I wake looking at it, and I’m back there—on the lake, feeling the breeze, listening to planks creak, and knowing that home doesn’t need foundations, just purpose.

Because life on water isn’t just about floating. It’s about connection—between people, seasons, spirit, and the living pulse of a shared ecosystem. And that lesson doesn’t drift away. It stays with you, steady as a boat on water.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.