Inside Naica’s Crystal Wonderland: Too Beautiful (and Dangerous) to Visit

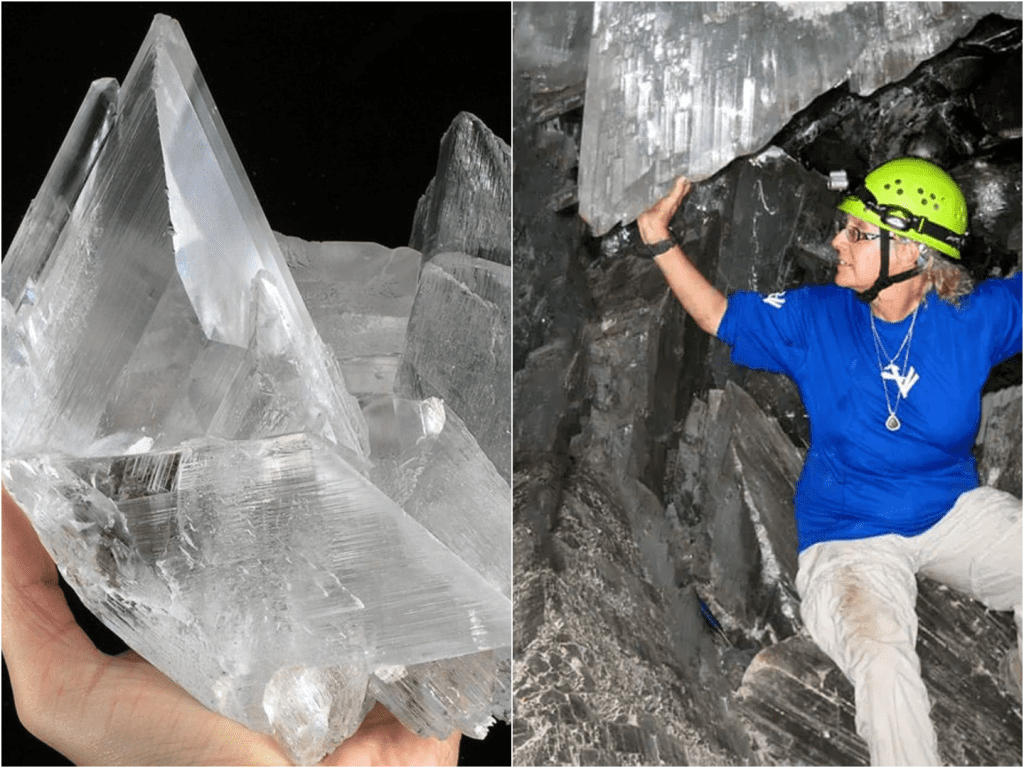

I’ll never forget the first time I saw photos of dazzling crystal caverns hidden 300 meters underground in Naica, Mexico. Imagine massive translucent beams, some nearly 12 meters long, jutting out of dark walls—hidden like a secret frozen world. The Cave of Crystals feels like stepping into fantasy, until you learn just how deadly it can be.

Discovered in April 2000 by miners drilling a ventilation shaft, this cavern was a total shock. They broke through and suddenly found themselves in a chamber filled with giant gypsum crystals—some estimated at 12 tons each. The size alone made the cave legendary, but deeper stories lay beyond the surface shine.

This place is breathtaking and brutal. Temperatures hover around 58°C (136°F) with humidity between 90 and 99 percent. It’s so steamy that sweat can’t evaporate. Heat and humidity combine into a deadly mix that quickly turns lungs into condensers—air so heavy and humid you can drown from moisture alone. Researchers wear refrigerated suits filled with ice and fresh-air systems, but even with that protection, they can only explore for 10 to 45 minutes before risking collapse. Layer in slippery crystal surfaces and narrow passages, and it becomes a place of wonder paired with real-life danger.

Scientists and explorers have shared powerful memories. Speleologist Penelope Boston, who entered the cave, described tears welling up as she touched the crystals, feeling utterly connected to something timeless. Another explorer said he could stay in the cave for only five minutes before feeling like he was dying. Their stories paint a picture of a place both hauntingly beautiful and spiritually overwhelming.

Then there are the pure science bits. Builds of gypsum began around 26 million years ago, when magma heated water rich in anhydrite. As it slowly cooled just enough, huge crystals formed over hundreds of thousands of years in perfect conditions. These crystals kept growing in near-perfect silence and darkness—until miners broke through.

Inside the crystals, researchers found pockets of ancient fluids with dormant microbes. In 2017, Penelope Boston’s team revived bacteria that had been trapped for up to 50,000 years. These microbes were unlike anything known before, distantly linked to life from volcanic soils in Kamchatka or Spanish caves. That discovery sparked hopes about life in extreme places—even on other planets.

By 2006, scientists from six countries were working in the cave, nicknamed Project Naica. They mapped chambers called Cave of Crystals, Queen’s Eye, Candles Cave, Ice Palace, and more—each stunning, each dangerous. But exploration had to stop by 2010, and by 2015 the mine flooded, refilling the caves with mineral-rich water. Now access is impossible—but water protects the crystals for future generations.

I spoke with one miner’s grandson who still visits the site’s entrance. He said, “It’s like a cathedral. Only you can’t breathe inside.” That felt fitting. A silent, glowing cathedral where life thrived in silence for hundreds of thousands of years.

No tourist can go down there now—not even scientists without special permission. It’s too hot, too humid, and too dangerous. Even industrial cameras failed—Mexican filmmaker Gonzalo Infante had to use a robot-mounted camera taking stills for hours to capture just 10 seconds of footage. National Geographic used that for a documentary, showing only a glimpse of this hidden world.

But why let it stay sealed? Because the moment the air shifts, the crystals begin to erode. Without the cave’s humid, sealed environment, they can crack or crumble. Think of Lascaux cave paintings in France—so fragile that tour guides had to be replaced with replicas to save the originals. Here, too, preservation matters more than popularity.

Today the site is flooding again, and the mine pumps are offline. The cave remains forever hidden, growing its crystals deeper in darkness. Someday, if another entrance opens, scientists might go back—maybe discovering even bigger crystals yet—but for now, Naica sleeps in underground water.

What stays with me is not just the wonder, but the tension. It’s a place so beautiful it stops your breath, but because of that beauty, it could kill you. It’s nature at its most grand and unforgiving. It feels humbling to think such beauty can hide in plain Earth, underground, protected by darkness and danger.

For most of us, Naica Cave will remain a story told through photos and articles—a reminder that Earth still holds secret wonders that are too intense to touch. But that’s fine. Some places are meant to be dreams, not destinations. And Naica’s Crystal Cave? It is the dream of beauty born in heat, darkness, and time.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.