The Door to Hell in Turkmenistan — A Crater That’s Been Burning for 50 Years

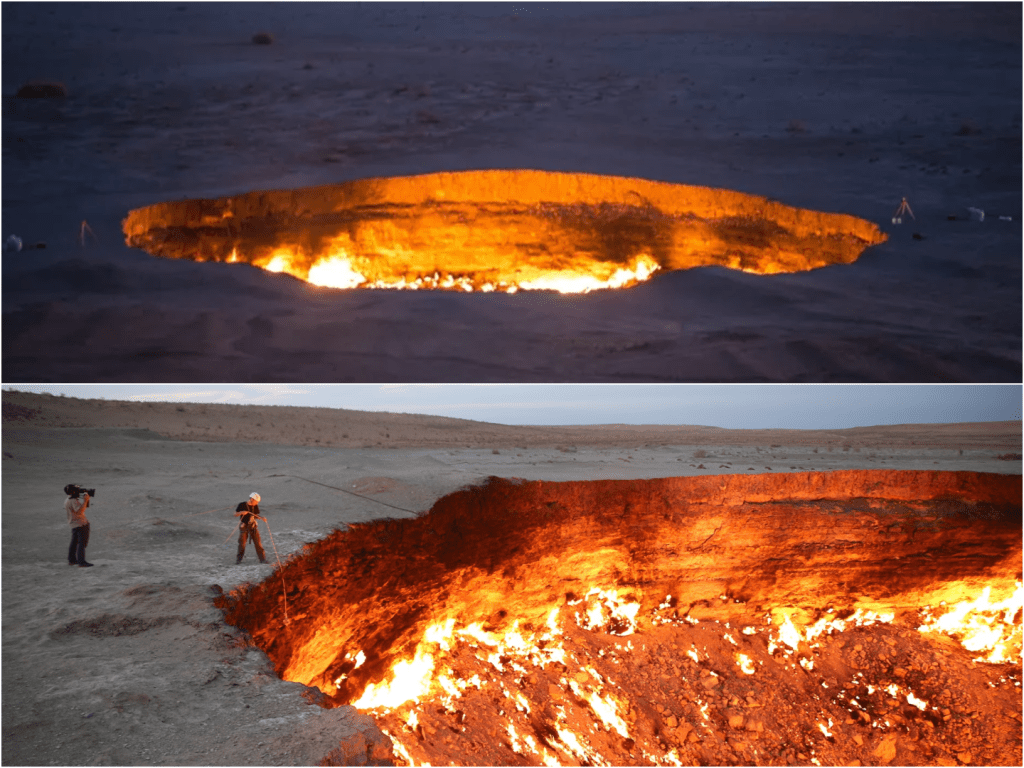

I’ll never forget the first time I saw that glowing, inferno-like crater in the Karakum Desert. A massive pit of fire in the middle of nowhere. It looked straight out of a dystopian movie, but it’s real—and it’s been burning for over half a century. This is the Darvaza gas crater in Turkmenistan, nicknamed the “Door to Hell.” It’s 70 meters wide, 30 meters deep, and flames have danced above its rim since 1971.

The story goes back to Soviet-era drilling. Geologists tapped into a huge natural gas cavern, and the ground collapsed miles of equipment into the hole. What followed was a cloud of toxic gas rising into the air. In a hasty move, they set it alight, hoping it would burn out in days. But what they thought would be a quick fix turned into decades of continuous flame. For 50 years, the pit has burned, illuminating the desert at night and mesmerizing visitors with its hellish glow.

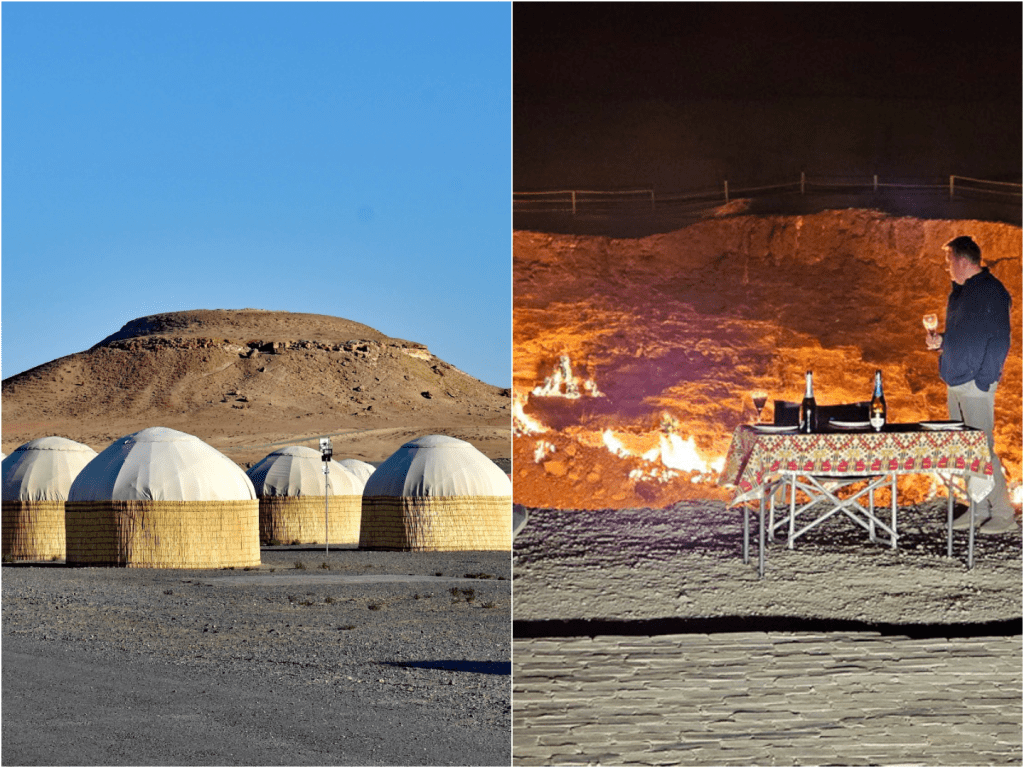

Getting there feels like a scene from a novel. First you drive off-road for about seven kilometers onto a sandy track. Yurts appear near the crater’s edge, offering shelter to travelers drawn by the bizarre spectacle. Visitors gather as dusk descends and the crater starts to shimmer. At night, flames reach 10 to 15 meters tall, the air smells of sulfur, and you feel heat like an oven. Locals call it “Shining of Karakum,” but for many, it truly feels like you’re standing at the gates of another realm.

Beyond its dramatic presence, the crater is a story of environmental reckoning. Burning methane creates carbon dioxide and soot, contributing to climate change. Turkmenistan holds massive reserves of natural gas, and letting it burn freely feels wasteful. In 2010, the president considered putting the fire out to improve resource use. Then in 2022, new plans to extinguish the flames and capture methane emerged as environmental concerns grew.

Recent reports suggest progress. By June 2025, the fire’s intensity fell by about threefold, thanks to wells drilled around the crater to redirect gas flow. Officials say the massive glow once visible from kilometers away is now much quieter—though small flames still flicker at the bottom. Scientists presented the findings at a hydrocarbon conference in Ashgabat, confirming the blaze is fading.

Despite this, it’s still a magnet for travelers. Adventurer George Kourounis became the first person to descend into the crater’s depths in 2013, investigating its extreme conditions and even collecting soil samples. He described feeling “like a baked potato” deep inside the rim, wearing a protective suit and breathing apparatus. Scientists are still interested in what lives in this scorching environment—microbes or “extremophiles” that might resemble alien life.

Visiting the crater means standing on the edge of an unfathomable void of flame and heat. It’s primal, surreal, and oddly spiritual. Around you, the desert stretches to the horizon, silent except for the roar of burning methane. Crickets chirp, small spiders hide in the shadows, and somewhere in the distance, the world seems normal again. That contrast makes the scene unforgettable—the hush disturbed only by fire.

But beyond the spectacle, there’s a deeper truth. This crater stands as a living monument to human error, environmental costs, and shifting priorities. Turkmenistan’s efforts to tame it show a shift from spectacle to responsibility. If the flames finally die, the crater’s story doesn’t end—it changes. It might become a silent scar or a monument to mistakes past. Or it could be repurposed, an engineering achievement of captured methane or a memorial to the Earth’s fragility.

One traveler shared on Reddit that some locals believe burning the crater would dim its mystique and hurt tourism. They worry about losing regular visitors who camp in yurts, gather stories, and marvel at flames that have lasted generations. Yet others hope the change brings cleaner air and better use of gas—because resources matter when global warming looms.

I visited in spirit through these stories, and I’m drawn between wonder and worry. This crater is both natural wonder and man-made warning. Standing at its edge, you feel small in the vast desert, listening to fire’s roar—and wishing you left a mark more constructive than combustion.

The Door to Hell has burned for over 50 years—it might burn longer, or it might go dark soon. Either way, it reminds me how tiny our time is, how powerful our actions can be, and how even the worst accidents can light up our collective curiosity. And for now, that fiery mouth still stands, challenging us with every flicker of flame.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.