How the Great Victoria Desert, Australia’s Biggest Wilderness, Thrives Quietly with Life, Culture, and Isolation

The Greatest, Wildest Desert Down Under

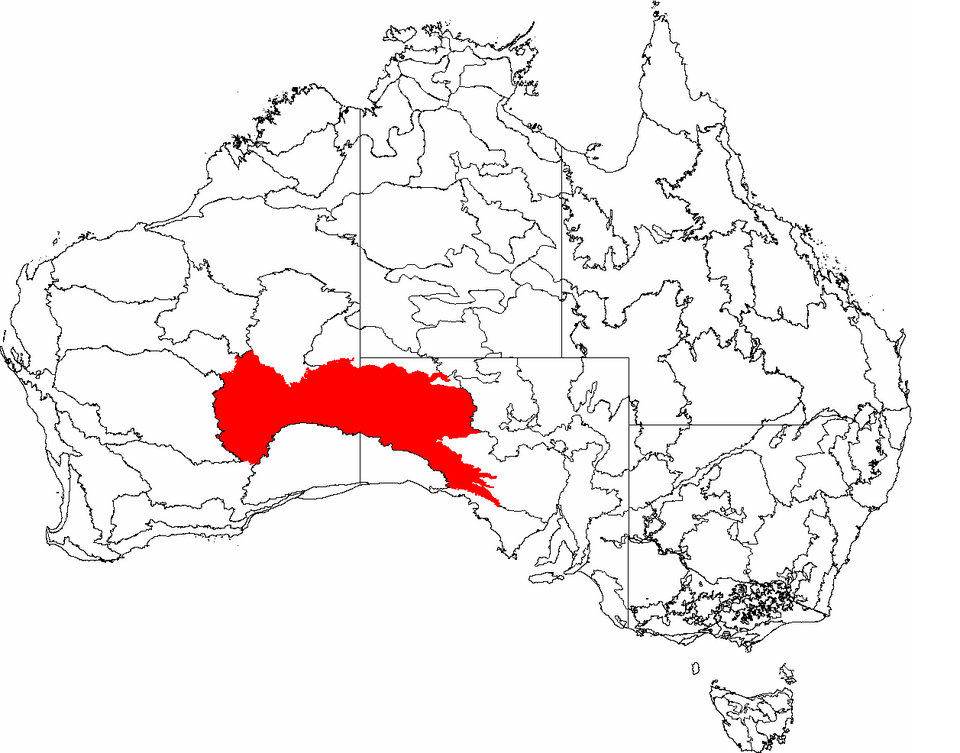

Imagine a land so vast that it makes Germany seem tiny. A place so remote you might spend a day driving without seeing another human. That place exists, and it’s called the Great Victoria Desert, Australia’s largest desert and the seventh-largest in the world. Spanning roughly 350,000 to 422,000 km², it stretches from Western Australia into South Australia—covering a region about the size of Britain, Germany, and Italy combined.

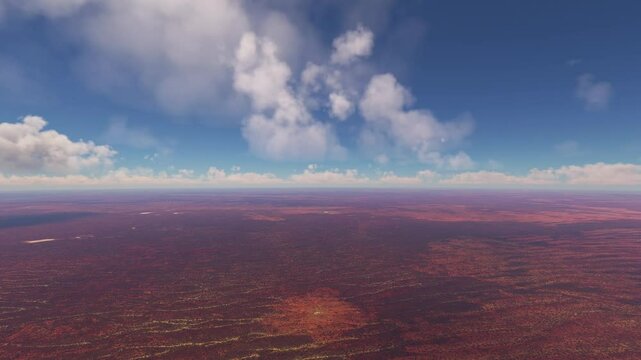

I first heard about it on a map. It appeared as a huge swath of reddish-tan between the Nullarbor Plain and the Gibson Desert. Over zooming maps, then photos, then stories… it felt impossible that a place so large could feel so empty. Most of it is remote Aboriginal land and crown reserves, dotted with few tiny towns, little tracks, and huge tracts that see no regular visitors. Some parts average only 200 to 250 mm of rain per year, unpredictable and brief—making it true desert. Evening temperatures in summer can drop to almost zero, while daytime soared above 40 °C.

Yet despite the harsh conditions, this desert hums with a fragile life of its own.

Where Survival Meets Story

Spinifex grass paints much of the landscape, shimmering like haze over the rolling dunes. Patches of hardy eucalyptus—marble gum and mulga shrubs—stand guard over salt lakes and gibber plains. When rains come in rare flushes, wildflowers bloom. The Sturt’s desert pea unfurls red petals against the rust-colored sand.

And the animals. Australia’s iconics stride here: red kangaroos, emus, and dingoes roam. But look closer and you find world-unique survivors: the great desert skink, the sandhill dunnart, the mulgara, even the southern marsupial mole—each adapted to scarce water and brutal heat with clever burrowing, nocturnal habits, and ancient resilience.

Indigenous culture threads through the quiet of this place: the Pila Nguru and Mirning peoples have walked this terrain for more than 24,000 years, shaping it with traditional burning practices, songlines, and connection to land. Their knowledge guides conservation efforts today—like fire management that protects dunnarts and seeds alike.

Explorers mapped it slowly. Ernest Giles named it after Queen Victoria in 1875, then walked it west to east. The desert tested him—heat, thirst, dunes. He wrote that everywhere was flat, silent, and motionless. In the 1960s and ’70s, Len Beadell cut roads through it. Even those “roads” remain rough four-wheel-drive tracks today—the Anne Beadell Highway, the Connie Sue, and others that stitch small jumps between distant fuel stops or communities.

And yet, despite its size, very little has changed. The area has limited grazing, no large towns, no sprawling farms. Thirty-one percent is protected in reserves like the Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve and the Mamungari Conservation Park, recognized as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Why This Desert Matters

Standing in the Great Victoria Desert isn’t about ticking a travel goal. It’s about noticing emptiness that feels full. A place stretched by wind and sky, where silence is not absence, but presence. Where life is sparse but real. Where the tiniest skink burrows, and ancient plants bloom after rain with stubborn color.

Climate change threatens it. Rainfall could become even more erratic. Traditional fire knowledge, slowly restored, helps—but the stakes are high. People worry about habitat loss, introduced species, mining, and wildfires. Conservation now means combining Indigenous insight and ecological science to keep this place alive.

In other words—not everything massive is built. Some of it is inherited. Some of it is left. The Great Victoria Desert is not a challenge to conquer. It’s a quiet education in time, adaptation, and awe.

I once sat on the salt-hard plain at dusk, sky fading from gold to lavender. No skyline, no buildings. A few stars. Spinifex sticks crackled slightly in the evening cool. It felt like stepping off the map. And yet I knew I was somewhere deeply mapped by a thousand generations. This desert is both a memory and a future, stretching wide, carrying stories that do not shout.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.