Why Alaska’s 47,000-Mile Coastline Makes It Feel Like an Island Universe—And Why That’s Worth Remembering

I first heard the fact on a crisp evening in Homer, watching the sun dip into Kachemak Bay, carving long shadows across the water. A friend said it almost casually—Alaska has more coastline than all of the other 49 states put together. I paused as the waves lapped the rocky shore. Suddenly, it felt meaningful, felt like an invitation to imagine what Alaska really is—and why it matters.

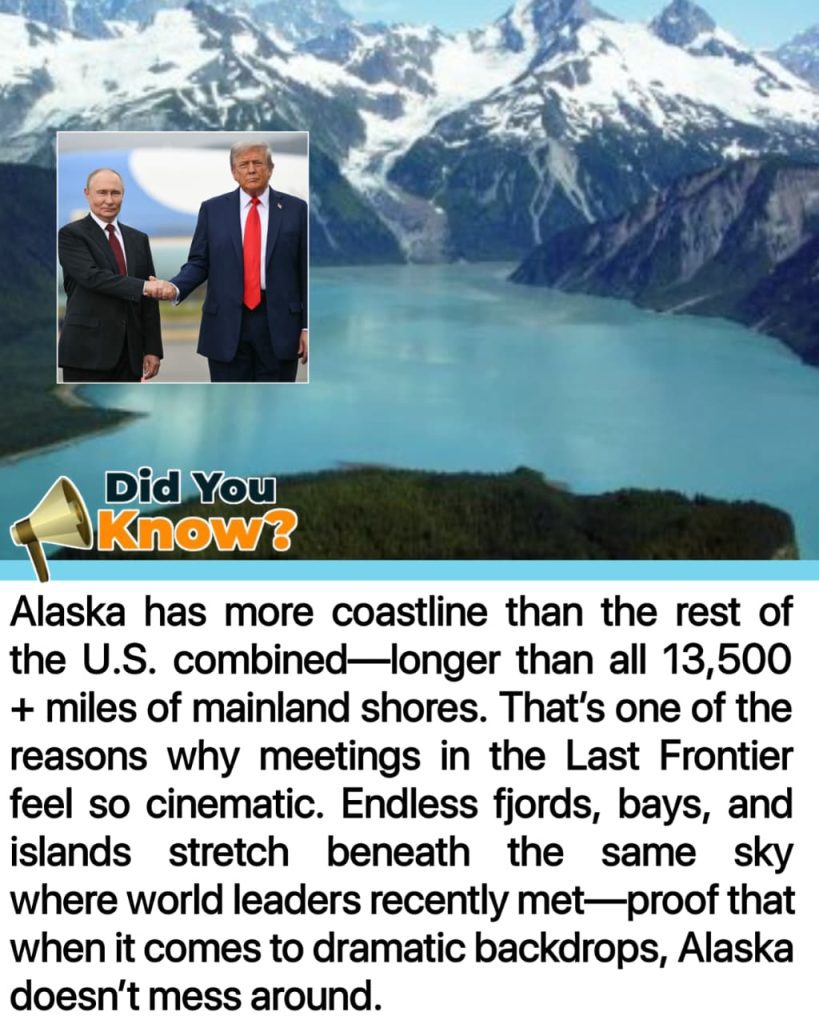

They say Alaska’s tidal shoreline stretches more than 47,000 miles, maybe even pushing past 46,600, depending on how the tides trace it. That’s not reclining across the map—it’s sprawling in endless fjords, skirting glaciers, threading through islands and peninsulas, tracing every inlet like a pearl necklace wrapped around tundra. For context, Florida’s shoreline is about 8,400 miles at the second place, and California barely hits 3,400 miles. Alaska is in a league of its own, and it wears that coastline like a crown.

As a traveler, this fact changed the way I saw the state. It’s not land with edges; it’s a liquid boundary where wilderness and tide meet. Much of the travel there isn’t by road—it’s by boat, floatplane, or heart. Communities often live on the water’s edge because there’s no real “inland” in the way most of us understand it. In southeast Alaska, the Tongass National Forest covers millions of acres, stitched together by mist and ocean, and connected only by ferry or wings, not highways.

That eve in Homer, I watched fisherman unloading king salmon from skiffs. The sea stains their boots; the air smells of brine and broken daylight. I thought about how Alaska’s life spins around water—subspecies of whales gliding past, eagles circling the capes, otters floating patient and sleek. I thought about how the roads stop, and the real journey begins where the asphalt ends and the tide carries you.

Alaska’s geography makes it a land built on scales we’re not used to. It’s a non-contiguous state that juts into Russian seas, borders not another state but two Canadian provinces, and lives in two hemispheres. It is both the easternmost and westernmost point of the United States. That long, jagged coastline is how it writes itself on the map.

That afternoon, I took a ferry to a tiny spit of land—just wildflowers and spruce and seabirds. There was no restaurant, no shop, just water reaching in on every side. People come here not for landmarks, but for moments—moments where skin remembers salt and lungs open into cold wind. They come to hear the horizon breathing.

Knowing Alaska’s shoreline is so vast shifts how you pack, how you plan, how you imagine. It’s not enough to say “coastal drive” because no road touches half of it. You book a cruise, you charter a kayak, you listen to a floatplane’s engine. You imagine meals cooked with chopsticks while the bow cuts into tides older than your suitcase.

And the entire narrative of the place changes. Alaska is not detached wilderness. It’s encircled, entangled, bordered by sea. Mountains and glaciers descend directly into tidewater. Each inlet frames a scene—brown bears salmon fishing under auroras, ice fields calving white thunder, lighthouses burning into midnight blue.

When I finally left, I carried that impression with me: Alaska is written by water. Not just part of the U.S., but a coastline-first state shaped by every wave. That rugged fringe is its spirit. And it’s wild enough to carry any traveler past their expectations.

Lena Carter is a travel writer and photographer passionate about uncovering the beauty and diversity of the world’s most stunning destinations. With a background in cultural journalism and over five years of experience in travel blogging, she focuses on turning real-world visuals into inspiring stories. Lena believes that every city, village, and natural wonder has a unique story to tell — and she’s here to share it one photo and article at a time.